Toronto might be slow when it comes to expanding transit and responding to the housing crisis, but it hurries to bulldoze historic neighbourhoods, filling them with glass-walled condos that will set you back 500k for 500 square feet. The glass buildings come attached with $7-a-drink shops, peppered with aesthetic gimmicks, and Torontonians will fall for a marketing gimmick as quickly as they fall out of it. If you can’t afford the boxes, you might have to drive, and drivers are always in haste, rushing to their destinations. The rules of the road are suggestions. Within such velocities of the city, Christina Wong’s Denison Avenue halts readers with a question: What about those who cannot catch up?

The multimodal novel opens in the mid-2010s when an elderly Chinese man, Wong See Hei, is grievously injured by a speeding SUV as he crosses Dundas Street West. When his wife Cho Sum finds that her lifelong companion is in a coma at the hospital, she barely has time to accept this fact before the doctor—who is annoyed that she speaks only Toi San Waah (Toisanese), not English—impatiently demands that she decide to terminate life support as soon as possible. See Hei passes away, leaving Cho Sum to deal with the erosion of their home, Spadina Chinatown. For the rest of the novel, Cho Sum grapples with twin losses of her husband and Chinatown; each intensifying the other. Hua Long Supermarket and Kim Moon Bakery, the two places Cho Sum and See Hei frequently visit, are both gone by the end of the novel. Spadina Chinatown is being quickly filled with banks and condominiums.

Behind See Hei’s death and Chinatown’s corrosion is the cruel urban project of Toronto. Toronto was never intended for Chinese lives. At the root of its construction is the settler colonial logic that maintains and reproduces processes of displacement and dispossession. Through the Toronto Purchase of 1805, the Mississaugas of the Credit were displaced by settlers, allowing Toronto to be established primarily for white, English, heterosexual, middle-class individuals and above. The city zoned and maintained the “undesirability” of specific neighbourhoods to house Indigenous, racialized, and low-income communities, including Chinatowns, Liberty Village, Mimico, Jane and Finch, Regent Park, The Junction, Parkdale, Riverside, and others. See Hei is killed from the hit and run because urban planners inject speed into Chinatowns and other “undesirable” neighbourhoods; these places are framed as commercial corridors in the eyes of the city and not residential areas that they are. Despite the odds, the inhabitants made these places their homes. They survived.

In the twenty-first century, settler colonial logic uses the process of gentrification to displace the inhabitants from their homes. The city, along with property developers, now frames these neighbourhoods as failing and in need of revitalization. Swaths of these racialized and/or working-class neighbourhoods are cheaply bought up, rebuilt, and remade for white, able-bodied, middle-class consumers to move in, while those who do not fit into the project will have to catch up (assimilate and grind harder) or get pushed out. The moral cover masking the logic of displacement, whether economic, cultural, social, or political, rests on the words “progress,” “revitalization,” and “development.” These words perpetuate the delusion that the people of these neighbourhoods were/are/have been individually responsible for failing to keep pace with a limited idea of progress, housed in mass “condoization” that somehow meaningfully moves Toronto towards a utopian future.

In Denison Avenue, Cho Sum’s grief challenges the notion that gentrification brings progress. Discriminatory urban planning, which includes gentrification, isn’t a happy story. There’s a profound sense of loss for inhabitants like Cho Sum, who has spent years calling Chinatown her home. Cho Sum’s grief resists Toronto’s demand for temporal progression into the future, as she consistently returns to the past when she remembers See Hei and Chinatown. Moments of grief are amplified through the poetic form. The enjambment and blank spaces convey Cho Sum’s sadness as a collective experience that is difficult to articulate in formal language.

Language is also at the heart of Denison Avenue and its concerns with who gets left behind. Progress in settler colonialism means culturally and linguistically assimilating into the dominant class, so knowing English is a temporal marker of being “on time.” At the same time, Indigenous and immigrant languages are framed as residuals of the past. In Toronto’s monolingual English space, accommodating diverse language speakers—seen in the case of the doctor being impatient with Cho Sum and the exclusion of non-English speakers in city planning in the novel—is perceived as a hindrance, not a condition of justice. To translate would mean patiently slowing down and doing the work to ensure everyone is on the same page, making the most equitable decision. Part of what makes the gentrification of Chinatown so harrowing is that the city’s decision-making process purposely excludes stakeholders through language.

In one scene after See Hei’s death, Cho Sum goes to a meeting discussing the future of Kensington and Chinatown. She feels completely excluded because they speak English and are unable to see Chinatown as anything but “dirty.” The experience prompts her to recall how See Hei also exercised his civic participation in the past. He’d attend the city planning meetings and try to make a difference. He becomes disillusioned after seeing how the powers of governance sideline Chinese residents who cannot speak English, excluding them from urban planning decisions that shape their homes. As Cho Sum poignantly realizes, “They told [See Hei] they were signs of/progress to come, but we knew it was/ progress that wasn’t meant for us” (65). Gentrification enacts the word “progress,” while ironically, the processes harken back to old racism that maintains exclusion and displacement of those who do not fit into the dominant class.

Gentrification of Spadina Chinatown is a repetition of history. Before the late 1950s, Toronto’s Chinatown was located in “The Ward” between Queen and Dundas, exactly where City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square are presently situated. The City of Toronto expropriated the land and demolished the commercial and residential area without consulting the Chinese community. As a result, the Chinese community settled in Spadina Chinatown and East Chinatown (located on Gerrard Street East). Racism maintains the illusion that the racialized voices don’t exist, when the truth is that they are not heard.

Denison Avenue’s power lies in giving voice to Cho Sum, which symbolizes the collective voices of those affected by the gentrification of Chinatown. Throughout the novel, Wong employs literary multilingual strategies to convey Cho Sum’s voice. Most of Cho Sum’s stream of consciousness is in English, while her speech is in Toi San Waah. Every time Toi San Waah orality is encoded through the English script, the subsequent English translation (known as the metalanguage) appears in parentheses. The aesthetic positioning of Toi San Waah against the English translations in the text centres Cho Sum’s consciousness and places the English dominant language in the periphery. Cho Sum’s interiority is centred and valued, reversing the societal logic in Toronto, where immigrants are often expected to work to make themselves comprehensible to the centring dominant class. The translations also slow down the narrative tempo in Denison Avenue. Wong makes the readers go through the text more slowly and carefully, as they must first read the original Toi San Waah before the English translation of Cho Sum’s dialogue. There’s a richness gained through the multiplicities and tempo, something that is lost in rapid gentrification.

Toi San Waah is also significant when considering the broader history of Chinese Canadians. The earliest generations of Chinese migrants to Canada in the nineteenth century were from Southern China. They were poor and spoke neither Cantonese nor Mandarin, which are considered language varieties of the dominant classes in China. Cantonese’s dominance is associated with the migration of Hong Kongers to Canada in the 1980s and 1990s, while Mandarin’s dominance is linked to the influx of Mainland Chinese in the 2000s and 2010s. Toi San Waah is tied to the histories of Chinese sojourners and their descendants who endured the history of exploitative work conditions in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway and anti-Chinese racism policies in the Chinese Immigration Act, 1885, and the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, leading to decades of families being separated and socioeconomic immobility.

These are the generations of people who endured the ghettoization of Chinatowns before these spaces were celebrated as evidence of Canada’s liberal tolerance of multiculturalism. The inclusion of Toi San Waah speakers importantly situates present-day gentrification of Chinatown within the more extended history of racism towards Chinese Canadians.

Cho Sum’s narrative voice richly reveals many endonyms, which are portals to alternate lingual landscapes of Toronto and their affective dimensions. She and See Hei fondly call Honest Ed’s Chaan Lau (層樓). Chaan Lau emphasizes Honest Ed’s vastness in physical size and generosity. Every holiday, Ed Mirvish would offer free turkeys. Every visit to the gaudy establishment is a win for Cho Sum due to its cheap bargains. Chaan Lau made Toronto home to Cho Sum and See Hei. In real life, for many working-class, poor students, elders, and immigrant families, Honest Ed’s was a lifesaver, enabling them to survive economically in Toronto. The closing of Honest Ed’s in the novel brings readers back in time to a pivotal moment in Toronto’s history in the mid-2010s, when the city lost something.

The mid-2010s marked the twilight years of iconic Toronto establishments: Honest Ed’s, the World’s Biggest Bookstore, The Guvernment, and Brunswick House. People could rely on these third spaces to socialize and have a good time without breaking the bank. These places have since been turned into condos or commercial developments. We’re a decade after these closures, and when you look at what Toronto is now, “progress” may be the last word you’d use.

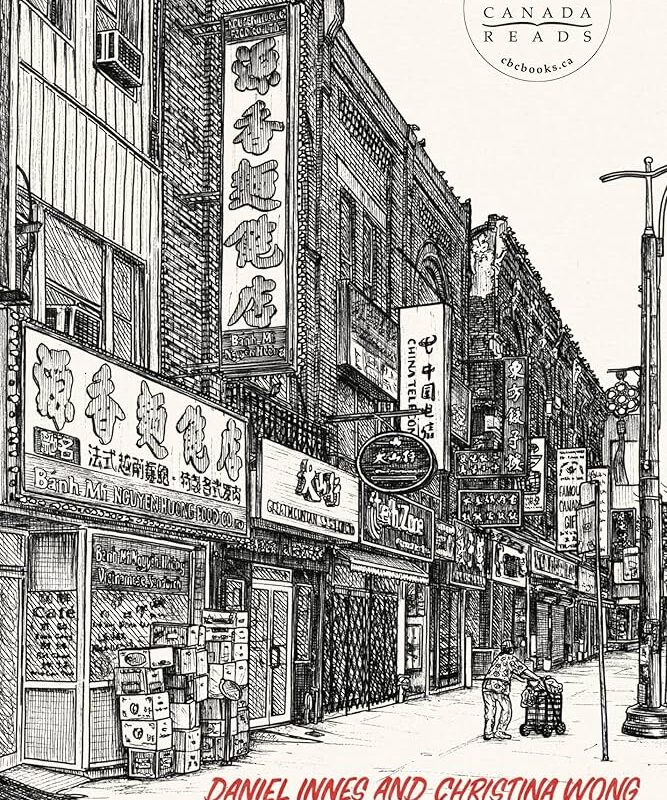

The other side of Denison Avenue’s narrative features Daniel Innes’s haunting illustrations, which visualize the structural changes of Spadina Chinatown over the years. The black and white lines accentuate the contrast between past images of Chinatown businesses and spaces and their present-day replacements, such as condos, banks, and ethnic franchises. Time is simultaneously suspended and accelerated. The illustrations encapsulate visual memories of the city’s urgent desire to forget Chinatown and its people.

As I flicked through the pictures, I paused at the sketch of the storefront of Kom Jug Yuen Restaurant on 371 Spadina Avenue. I remembered how, as a broke student in the early 2010s, Kom Jug (as known by the locals) was a lifesaver. They had a menu, but you were never going to get what you ordered. You’d accepted this caveat because they’d load the take-out container with as much meat and rice as possible for $5. The food got you through the day. The book juxtaposes the sketch of the restaurant with its replacement, CoCo Fresh Tea & Juice, a boba tea franchise. Although it’s one of the cheaper boba teas in the market, $5 will barely get you a tea drink here. Whereas Kom Jug was a mom-and-pop business nourishing the working class and economically marginalized individuals, CoCo represents conspicuous consumption, prioritizing display over function.

In the neoliberal narrative of Toronto, CoCo, compared to Kom Jug, signals progress. Bright neon lights. The place came with a business plan. Boba tea has been McDonaldized into a standardized procedure. Ethnic commodities are now standardized franchises. Gone are the days when boba tea was locally owned, cost $2, and had a powdery texture.

Maybe it’s a sign of progress. The other side of gentrification is internal. Asian Canadians who did catch up. They rose to become a middle- and upper-middle-class consumer base, enabling them to start franchises from ethnic commodities and pay $7 for a drink. As Cho Sum observes on Denison Avenue, many of her neighbours sold their businesses and houses in Chinatown. They bought houses in Markham, North York, Richmond Hill, and Scarborough, reflecting the desires of many Chinese Canadians who want to “make it” to the Canadian middle class. The problem is that when these members cash out, they leave the community’s long-term survival vulnerable to gentrification.

And what about those who cannot catch up? In the narrative portion of Denison Avenue, Cho Sum walks around Chinatown and the adjacent neighbourhoods, collecting recyclables and connecting with the community. She makes light of every little detail she sees in her narrative present. She observes life’s sweet bitterness. Remaining rooted in the present, Cho Sum is not chasing the promise of a future with more, more, more. The recurring narrative action of walking decelerates the cutthroat pace of our neoliberal present, where everyone hurriedly moves through their present to dream of a future that never seems to arrive. In the present-day illustrations, Cho Sum appears as a recurring figure who walks along the changes of the city. She is a small, crouched, elderly figure wearing a polyester shirt and pushing a trolley. The structures around her visually overshadow her. The cars and people may outpace her. However, her consistent silhouette is a reminder that the people of Chinatown remain, despite the velocity of all that has happened.

Monique Attrux

After spending two decades in Hong Kong where she was born and raised, Monique took her passion for literature with her to Toronto, where she became a PhD candidate at York University. She is deeply passionate about exploring how language shapes and reflects ethnic identities in the realm of literature. Her academic journey has been enriched by the generous support of several scholarships: York Entrance Scholarship (2020), the Vivienne Poy Hakka Research Award (2020), the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (2021), the SSHRC Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canadian Graduate Scholarship (2022), the Canada-China Initiatives Fund (2022), and the Clara Thomas Scholarship in Canadian Studies (2023). She is shaped by Evelyn Lau, Roxane Gay, George Orwell, bell hooks, and Audre Lorde. Although she has a bias for clean prose, her reading tastes are eclectic, and she has yet to claim a favourite author. In time, she hopes to dabble in some creative writing of her own, but for now, she will enjoy the sweet escapes of getting lost in other people’s wor(l)ds.