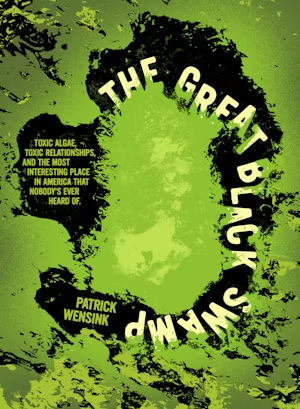

The Great Black Swamp: Toxic Algae, Toxic Relationships, and the Most Interesting Place In America That Nobody’s Ever Heard Of (Belt Publishing, 2025)

Deep time, as impossible as it is to comprehend and as unsettling as it is to contemplate, at least gives you some comfort from sheer remove. Yes, it is uncanny and awesome to think that the Great Lakes area was, tens of millions of years ago, a warm shallow ocean filled with weird fish. And, yes, it can be humbling to think of the way that time grinds on without caring about our tiny contributions. But that very distance can make time seem like an old sleeping god.

What can be even more unsettling to think about are turbulent changes happening in shallow time. That the land we know and are comfortable with, and think of as permanent, has undergone near-geologic upheavals in the span of a few paltry human generations. That our framework for “unchanging” — essentially, because something looks more or less the same as when we were kids — obscures revolutions underfoot. When we think about the rapidity of changes, and the potential for damage that humans have done, shallow time feels more of a drowning terror than deep time.

It’s these recent and remarkable changes that are explored in Patrick Wensink’s new book, The Great Black Swamp: Toxic Algae, Toxic Relationships, and the Most Interesting Place in America That Nobody’s Ever Heard Of. If you count yourself among the nobody who has ever heard of the Great Black Swamp, one of the most remarkable and important natural features in recent Midwest and American history, don’t feel bad: it no longer really exists. And that’s exactly the problem that Wensink outlines in his charming, personal exploration.

What was the Great Black Swamp? It was (and in some strange way we’ll get to later, still is) an enormous, deadly, nearly impenetrable swamp in Northwest Ohio, a stinking, sinking wetland stretching southwest from Lake Erie toward Indiana. It’s ok to use state names here, because the swamp isn’t primordial history: it was still around while the land was renamed, and indeed into the 20th century.

So why don’t we know it? Why don’t we have to drive around it? Because, as Wensink explains in his book, in order to cultivate the land, the swamp was drained and destroyed. And what is left is Northwest Ohio, which, if you’ve ever driven through it, seems like the least wild place in America. This tension is at the heart of Wensink’s work. As he says, while hacking through a tiny preserve:

“You wouldn’t know it by looking around today at the vast, agriculturally abundant Northwest Ohio landscape, but this place was once so prehistorically wild and deadly that it took nearly a century of struggle to finally bend this land to Manifest Destiny’s will. The process was a nightmarish undertaking, filled with suffering, broken hearts, death, and both our best and worst American impulses. Today, outside of small preserves like this, it seems like this landscape was simply born a million acres of perfectly level fields of corn, soybeans, and wheat. Growing up, that’s what I always thought.”

Wensink, as you can tell, was born and grew up in Northwest Ohio, a small farming village called Deshler, whose population was small enough that “how many people died or went away to college that year” could make a measurable difference. Deshler is about an hour away from Toledo, which was the big city for Wensink.

Toledo holds a special place in Wensink’s heart. Indeed, the book opens with the story of the town’s uproar over John Denver’s “Saturday Night In Toledo Ohio” (“it’s like being nowhere at all”). Denver, the most harmless man that ever lived, became a municipal villain in the 70s, before a reconciliation made him a civic hero. It’s a goofy story, but a telling one for Wensink.

Toledo has been dying for decades. Its post-industrial decline has left half-used industries along the lakefront, and, driving through, one is never certain what is crumbling and what is still smoking along. But that’s nothing compared to what it faced in 2014, when an enormous toxic algae bloom erupted in Lake Erie, and made all the water in the town potentially deadly.

For days, no one could use taps. Bottled water became like gold as the town went dry. While the situation was resolved in a few days, it was a shattering and terrifying vision of what can go wrong. An entire city suddenly parched, where the worst-case scenario is that tens of thousands could have died simply by getting a glass of water from the sink or opening their mouth in the shower.

Why did that happen? Partly because climate change has made for warmer water, where algae can thrive. Partly because of the industries still polluting Lake Erie. But largely because the Great Black Swamp was no more.

To sum up, quickly: to “settle” Ohio, the swamp needed to be drained. It was an obstacle to crossing the country. Using clay tiles, and long narrow ditches running toward the rivers and Lake Erie, and logging, and painstaking backbreaking work the swamp was eventually drained and the underlying soil was some of the richest in the world. It became incredibly important farmland.

But, as Wensink explains, that had a few consequences, all exacerbated by near-term thinking. The book takes off through farmers moving to a near monoculture of corn, with some wheat and soy, encouraged by Progressive-minded planners to focus on what would make the most money the quickest. But this quickly ruined the soil, so farmers had to start using phosphorus-based fertilizer. Lots of it. And the drainage ditches that went toward Erie carried that phosphorus with them.

Algae feeds on that. And in 2014, it feasted. And a city nearly died.

Wensink describes all of these developments with a light hand and a storyteller’s eye. We learn about the push for corn, the intricacies of laying drainage tile and the machines that made it possible, the roads built through the swamp, the science of algae, and much else. He himself is not an expert in any of these fields, but a curious reporter, a magpie researcher, and a witty, self-effacing companion, bringing us to meet experts as we learn along with him.

Throughout the book, we learn of the contradictions inherent in the land. The changes that made the region able to produce food are the same ones that brought it to its knees. What brought life nearly became death.

This, then, is the story of Northwest Ohio, but also of the Great Lakes, and a world rushing into a changing climate. We have changed so much, so quickly, without understanding or caring what that will mean. We carved drainage ditches, pointing them toward the water, but not thinking about the futures they carried.

It is hard to think of Northwest Ohio as having this black and tangled land, so tree-choked that it felt as night during the day. If you’re having an elegant dinner with a charming and beautiful companion in suburban Perrysburg, you wouldn’t think that a few generations back carriages were lost in the deep and sucking mud. But strangeness lies just below.

Winsink plays with this idea as he weaves a partial memoir through his history. A “weird, artistic” kid in a time and place that rewarded neither, he felt removed by the flattening monoculture, even as he still thinks of it as home. It is that impulse to flatten that led to the swamp being destroyed. But just as Wensink the adult can still describe himself as weird and artistic — unflattened — the swamp is still below.

The land, the region, in many ways still needs the swamp and is adjusting to not having it. It no longer absorbs the chemicals, sending them instead unfiltered toward the lake. This isn’t conscious, of course; there’s no capital-N Nature making decisions. But when you change — transform entirely — in a matter of decades an ecosystem that has lasted thousands of years, there is bound to be blowback. The Great Black Swamp may no longer be there, but its absence is just as deadly.

The swamp is almost impossible for us to picture, in the same way that anything before we can remember seems as alien as the ancient ocean under our feet. That idea of permanence is dangerous, because it makes it hard for us to see what’s coming. It makes it hard to think of our drinking water blooming with toxic flowers. It makes it a work of painful imagination to realize that the land can transform as quickly as we pretended to tame it. It makes us blind to the idea that this time of abundance, of rich soil and drinkable water and fully-stocked stores, can prove to be shallow.

Brian O'Neill

Brian O’Neill is a freelance writer living just north of Chicago, along the lake. His focus used to be on international politics, specifically in the Middle East, where he specialized in Yemen. His writing on that topic led him to explore the relationship between the environment, natural history, and current events, a theme which has carried through his work. More recently he’s shifted from the Middle East to the Midwest, with many of the same themes. Brian has written about books for The Chicago Review of Books, The Cleveland Review of Books, Necessary Fiction, Yemen Review, and other publications. Understanding the region, the environment, and the people inside it is his passion and project.