In western Lake Erie, on the south shore of Kelleys Island, a limestone rock covered with petroglyphs holds a few clues as to the first humans to enter the area.1 Native American tribes had traveled the freshwater lake, hunting and fishing, and some of their group left their stories on the rock. The first Europeans who explored the area later gave the lake the name “erie,” an adaptation of a word from the Iroquois tribe that lived along its south shore.

I grew up in Erie County, Ohio, and on a clear day can see Kelleys Island from the rooftops of the native limestone buildings in the county seat of Sandusky. There were other notable landmarks such as Johnson’s Island, which held a prison camp for confederate officers during the Civil War; Marblehead Peninsula, that enclosed the western end of Sandusky Bay; and the steel monsters of Cedar Point, roller coaster capital of the country. I took for granted that we could drive down our city’s main street, Columbus Avenue, with a view of the waters of Sandusky Bay and Lake Erie beyond.

What I did not appreciate at the time, was the happy accident of geography, of being part of what Walter Havighurst called “the land of the inland seas.” My world was fresh water, beaches, islands, and industrial towns of Ohio and Michigan. The ancient Romans believed geography shapes identity. I agree. The Great Lakes shaped both the identity of the early Native American tribes on Kelleys Island as well as my own.

While I’ve now lived longer in the mid-Atlantic region than in the Great Lakes, the irony is that the geography of my first 20 years has embedded an urge to bring me back to the freshwater shores of the inland seas every summer.

This is a personal essay of how the Great Lakes has shaped my identity.

***

French explorers and trappers, including the explorer, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, sailed into the Great Lakes with the remote idea they still might find a passage to China. With the arrival of the French explorers and trappers in the late 1600s, they discovered that Sandusky Bay’s natural attributes made it a popular location as a trapping and trading post. A French map of 1720 shows a body of water called Lac Sandouské (present Sandusky Bay).2 The British later wrested control of the Great Lakes from the French and adopted the local Wyandot name for the land as sandusti, meaning “land by the cold water.”

The settlement of Sandusky opened up at the end of the Revolutionary War as the first portion of the Northwest Territory, created in 1787 by congressional ordinance. Most remarkable of all was that the ordinance did something the U.S. Constitution had not been able to do—explicitly ban slavery throughout the territory.3

Ohio had been admitted as a state to the country in 1803 but was still only a handful of small settlements along the Ohio River. Sandusky anchored the westernmost point in what was initially called Connecticut’s Western Reserve. Sandusky’s section of the Western Reserve was known as “the Firelands” because it was set aside for Connecticut residents whose towns had been burned during the Revolutionary War. The Firelands name stuck and has carried on to the present, with schools, hospitals, apartment complexes, and businesses using it in their names. Erie County had the Firelands Medical Center and The Firelands Manor Apartments.

Sandusky and the western islands continued to be a strategic point in the war of 1812. A young American naval officer, Oliver Hazard Perry, built a flotilla of gunboats at Erie, Pennsylvania, and defeated the British near South Bass Island (known as Put-in-Bay). Perry’s famous report of the battle, “We have met the enemy and they are ours!” was his legacy from the Battle of Lake Erie. His victory in 1813 drove the British from the Great Lakes.4

With peace on the lake, Walk-in-the-Water became the first steamship to bring new settlers to Sandusky in 1818, the same year the name was officially registered with the county. Thus 1818 marked the city’s founding year.5

The first settlers were New Englanders, a mix of Presbyterians and Congregationalists, who wanted even greater independence from the old settlements and sought a new start. Their religious devotion planted the early seeds of abolition and later formed a critical link on the Underground Railroad to freedom across Lake Erie in Canada.

One of Sandusky’s “founding fathers” was Oran Follett, who joined the American Navy at Lake Ontario working as a “powder monkey” at the age of 146 on the sloop Jones and fought in the Battle of Lake Erie.7 Follett reportedly overheard the American Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry remark that Sandusky Bay was the best port on Lake Erie, if not on the entire Great Lakes. The remark must have stayed in the teenage Follett’s mind.

After the Battle of Lake Erie, Follett returned to Sandusky to start a new life. He quickly realized the value of Sandusky’s location and chartered Ohio’s first railroad: The Mad River and Lake Erie Railroad.

Follett went on to lead Sandusky’s growth for the next 60 years as a business, political, and civic leader. He was president of the Sandusky Board of Education, superintendent of the Ohio Board of Public Works, and president of the Sandusky, Dayton and Cincinnati Railroad. He continued to use his writing skills, serving as editor of the Ohio State Journal as a means to fight slavery and build a party of resistance. He would later be instrumental in the development of the early Republican Party and in bringing Abraham Lincoln to national prominence.

***

Sandusky’s location on the water had also been a factor in attracting my father to take his first job there. He had grown up in a small town in Michigan and at 15, worked on lake boats traveling between Detroit and Buffalo shoveling coal. After serving in the U.S. Navy (at the end of WWII) and graduating on the GI Bill from Wayne State University in Detroit, he took a job as a salesman for a metals company in Sandusky, where he was attracted to the sailing community. He joined the sailing club and raced Flying Scots open cockpit boats and, later, larger sailboats in the Port Huron-to-Mackinac races.

His love of the lakes was passed down to me early on. As a kid, he would drive me around town on Saturdays and Sundays and with the water as the main entertainment. We would stop at the Jackson Street Pier on Water Street and watch the big freighters pulling into the channel and loading up with coal on the east side of town. Great Lakes freighters, simply called boats by those who worked on them, had distinctive stretched bodies with bridges at the front and superstructure in the back. And in the winter, he would drive to Battery Park, and we would watch the ice boats sail across the frozen bay, moving close to 70 mph as they heeled over on two blades.

To my young imagination, Sandusky’s coal docks were like a collection of slow-moving steel monsters. Giant cranes with large scoops that resembled a 50-foot-tall, metal praying mantis unloaded 600-foot ships. Dark skeletons of steely insects moved slowly and deliberately, dipping into the hold of a ship and scooping out coal for stockpiling.

The other monster was a black, steel tower we called the “coal dumper,” nearly 100 feet high, that looked like a hulking dinosaur skeleton. The inner workings of the coal dumper held a track with a steep incline, like a ski lift, that used a steam-powered push car to push individual train cars, fully loaded with coal, to the top of the ramp. At the top of the incline, the train car would be picked up, like it was part of a toy train set, and the contents dumped into the hold of the freighter docked below. Cars could be picked up and dumped at one per minute.

The Pennsylvania Railroad found Sandusky’s location ideal to bring their coal up from southern Ohio and built three slips that could handle ships up to 600 hundred feet. By the time my dad and I would watch it, the steam-powered pusher car had already been working tirelessly for the past 60 years. Photographers used Sandusky’s coal docks as a backdrop for orange and red sunsets blossoming at the western end of Sandusky Bay.

In the summers, our family never left the Great Lakes. We would go swimming on Cedar Point Beach and watch Independence Day fireworks put on by Cedar Point Amusement Park. My father would entertain business clients by taking them with their families and ours on the company cabin cruiser to Kelleys Island’s Glacial Groove Park and Perry’s Monument on South Bass Island. We fished for Lake Erie perch and ate perch sandwiches for lunch.

For our vacations, my father would drive my mother, sister, and me to the northern Great Lakes, Michigan’s Leelenau Peninsula, the little finger of Michigan’s mitt. It was where my parents, aunts, uncles, and cousins gathered every year— for two weeks of family time—in rented cabins on the shores of lakes that had been carved out during the last Ice Age, some 12,000 years ago.

The first time we arrived late at night in a full gale blowing off Lake Michigan—cold winds that whipsawed the tall pines along the shore of North Lake Leelenau. This seemed like a wild country. Even though I could hear the urgency in my father’s voice telling us to unpack the car, I could see the excitement in his face, like a little boy charged by force of the storm. That night we curled up in the stone and wood cabin as my father built a fire in the granite fireplace as the rain poured down outside.

Lake Michigan made such an impression that at the end of my second Michigan vacation, I went down to the lake and filled a jar of water and a plastic bag with sand to take home with me. I wanted to be tied to the land of the lakes with a year-round symbol to look at in my room at home.

In November 1975, as I was getting dressed for school, my mother told me that the local radio station, WLEC, had reported that the lake freighter Edmund Fitzgerald had been lost, with all hands, struggling to cross Lake Superior in a gale. I was an eighth-grader at Huron’s McCormick Middle School, and we lived a few blocks from Lake Erie. Outside a nor’easter was wildly shaking the branches of the trees, stripping them of what leaves were still left. Riding to school that morning, I can remember looking out the school bus window seeing Lake Erie churned with white caps by the near-gale-force winds.

At the time of the first news report, very little was known about the freighter beyond the fact that it was carrying taconite iron ore pellets from Minnesota’s Mesabi range to a steel mill near Detroit. This was scheduled as the ship’s final voyage of the season, where it was to move on to Cleveland and tie up for the winter. The Edmund Fitzgerald had disappeared from radar in a moment. Maritime experts theorized that the hull likely snapped in half by the immense stress of the waves on the long lines of the ship loaded with thousands of tons of iron ore.

Newsweek magazine reported the tragedy on November 24, 1975, in an article, “The Cruelest Month,” reporting November had a long history of ship disasters on the Great Lakes. The story brought national attention to the disaster, surprising the rest of the country who had little familiarity with the dangers of the inland sea.

Canadian Gordon Lightfoot, a devoted recreational sailor who kept his own boat on the Great Lakes, was among the millions who read the Newsweek article, and the next month he wrote and recorded “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” The song still has special resonance among the port cities of the Great Lakes, including Sandusky, if not with a generation of people who at the time listened teary-eyed to the news of the devastating loss of dozens of lives in an instant.

In my freshman year of high school, I became obsessed with writing a report for my English class on shipwrecks of the Great Lakes. But my teacher told me it was too broad a topic and to look at limiting my paper to shipwrecks of Lake Erie, of which there were hundreds. I soon discovered Walter Havighurst’s book, The Long Ships Passing: The Story of the Great Lakes. His was the first book I found in the school library, and it opened my imagination to the stories of the Great Lakes and, later, to the stories of my corner of Ohio and its importance to the country.

I also discovered Havighurst’s books on the history of the Great Lakes and the stories he told of its settlement and importance to the rest of the country. In The Land of Promise, he wrote of Walk-in-the-Water, the first steamer on the Great Lakes named after a Wyandot Indian chief that cast off from Buffalo in 1818 and made one of its first ports of call in Sandusky. A drawing of the boat was used as the symbol for the city’s sesquicentennial in 1968, appearing on coins, certificates, and banners.

When I graduated from law school, I moved to the east coast, started a job, married, and started a family. Having a child awakened in me a desire to reconnect with the Midwest. I convinced my wife, who grew up a New Englander in western Massachusetts, to spend two weeks of our summer vacation with our 1-year-old daughter in northern Michigan. My wife knew Cape Cod as a place for summer vacations—but the Midwest? I promised freshwater lakes, islands, and sand dunes. With that, we booked a cottage on northern Lake Michigan’s Beaver Island, where our daughter took her first steps. We returned for more summers where she learned to ride a bike at the summer lodge in the Leelenau Peninsula—the same place where some of my family had been going for the past 50 years. Another summer, we stayed at the iconic Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, overlooking lakes Huron and Michigan.

Our vacations to northern Michigan were in contrast to where our Washington area friends and co-workers took their vacations—usually traveling east to the Delaware and Maryland shores, or the Outer Banks of North Carolina. There was always a sense of bewilderment when I told our neighbors we had driven 15 hours to northern Michigan.

I’ve been returning every year, wanting to see more of the Great Lakes. Ever since I looked at my first map of the lakes, I wanted to travel to its far north, to Isle Royale in Lake Superior. Three years ago, I made my first attempt chartering a 50-foot sailboat and hired a skipper from Bayfiled, Wisconsin, but the fortunes of the lake decided it was not my time to visit. Between mechanical issues and strong squalls, we were forced to turn around. We adjusted our plans and for the next three days we explored the Apostle Islands.

Superior continued to captivate me. I discovered the books of Louise Erdrich, a member of Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, a tribe of Ojibwe peoples who wrote of the Ojibwe’s ties to the south shore of Lake Superior. In her Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country, Erdrich traces her travels in the western end of Lake Superior. I even read her children’s series The Birchbark House, The Game of Silence, and The Porcupine Year, that incorporates elements of Ojibwe myths and legends. I wanted to channel the love of the Ojibwe for the lakes through my own senses.

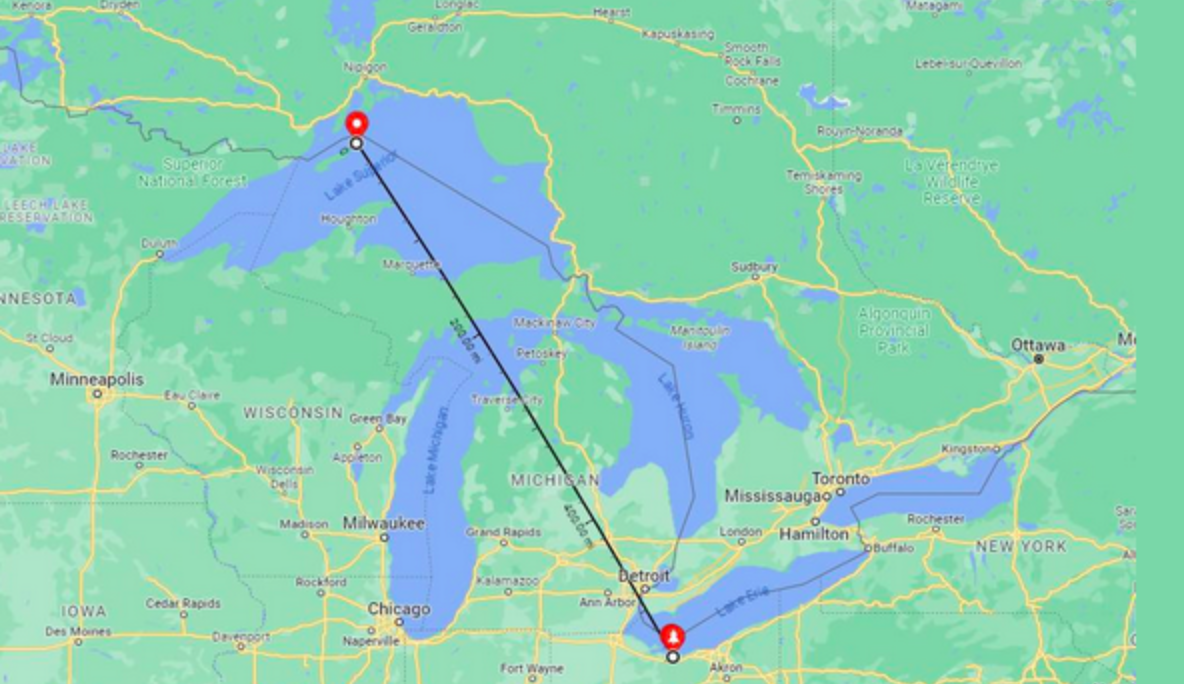

The year after my failed attempt to reach Isle Royale, my wife and I successfully traveled by sea plane to the island for a week of hiking and observing the wildlife. When we returned from our vacation, I realized we had visited the northern and southernmost points on the American side of the Great Lakes, with visits to Michigan’s Isle Royale, in the north and Old Woman Estuary, and Erie County, Ohio, in the south.

And this past year, we traveled to Michigan’s Keewenau Peninsula to stay in a cabin in Copper Harbor, Michigan’s northernmost point.

I don’t expect I’ll stop my annual pilgrimages to the Great Lakes. The geography is part of my identity.

Endnotes

- Charles Frohman, A History of Sandusky and Erie County (Columbus: The Ohio Historical Society, 1965), 2–3.

- Writers’ Program of the WPA, Lake Erie Vacationland in Ohio: A Guide to Sandusky Bay Region (Ohio State Archeological and Historical Society, Columbus, OH, 1941).

- Article VI of the ordinance. The history surrounding the ordinance was described in David McCullough, The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2019).

- Harry H. Ross, Enchanting Isles of Erie: Historic Sketches of Romantic Battle of Lake Erie, Oliver Hazard Perry. Put-in-Bay, Lakeside, Kelleys Island, Middle Bass, Johnson’s Island, Catawba, North Bass, Cedar Point, Sandusky, Port Clinton, other Islands and Resorts (H. H. Ross, 1949), 9–12.

- Later, Huron County was divided into two counties, with Erie County being the second county.

- Powder Monkey is a nineteenth century naval term of art for a young sailor who carried gunpowder from the powder in the ship’s hold to the artillery pieces.

- Helen Hansen, At Home in Early Sandusky, Foundations for the Future (Sandusky, OH 1975), 1.

John Kropf

John Kropf is the author of three books including most recently, A Midwestern Heart, his first collection of poems published by Bottom Dog Press (2024). His writing has appeared in The Middle West Review, Belt Magazine, The Washington Post, and elsewhere. He is a member of the Society of Midland Authors.