Baggage

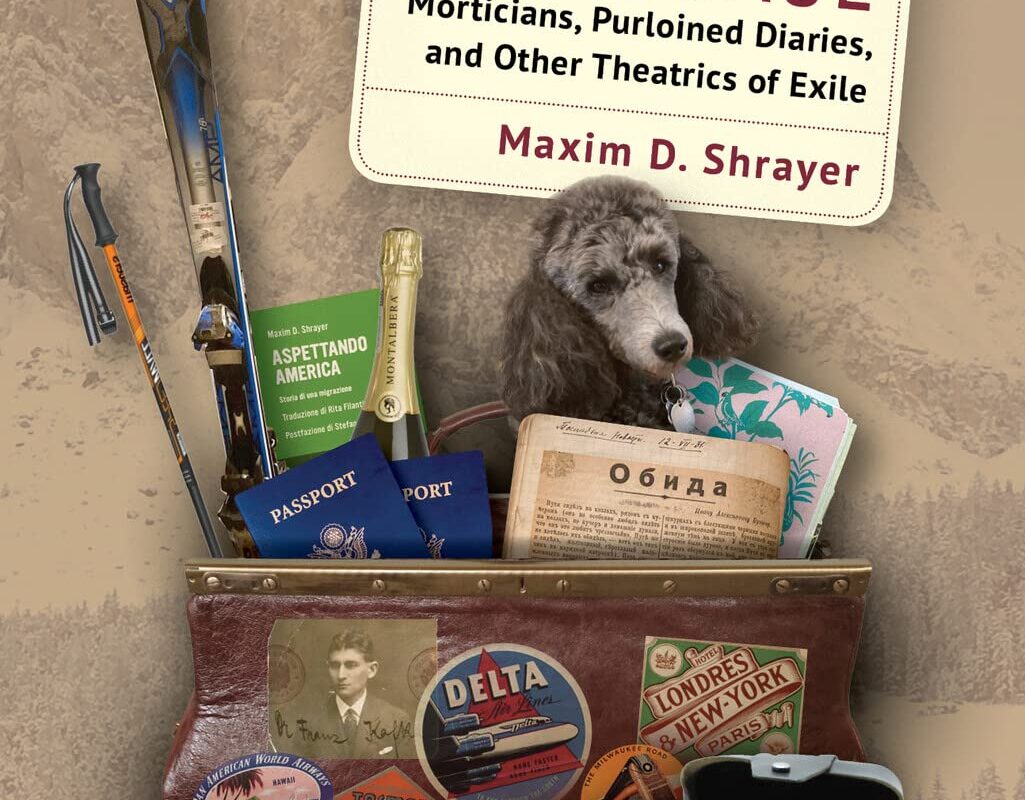

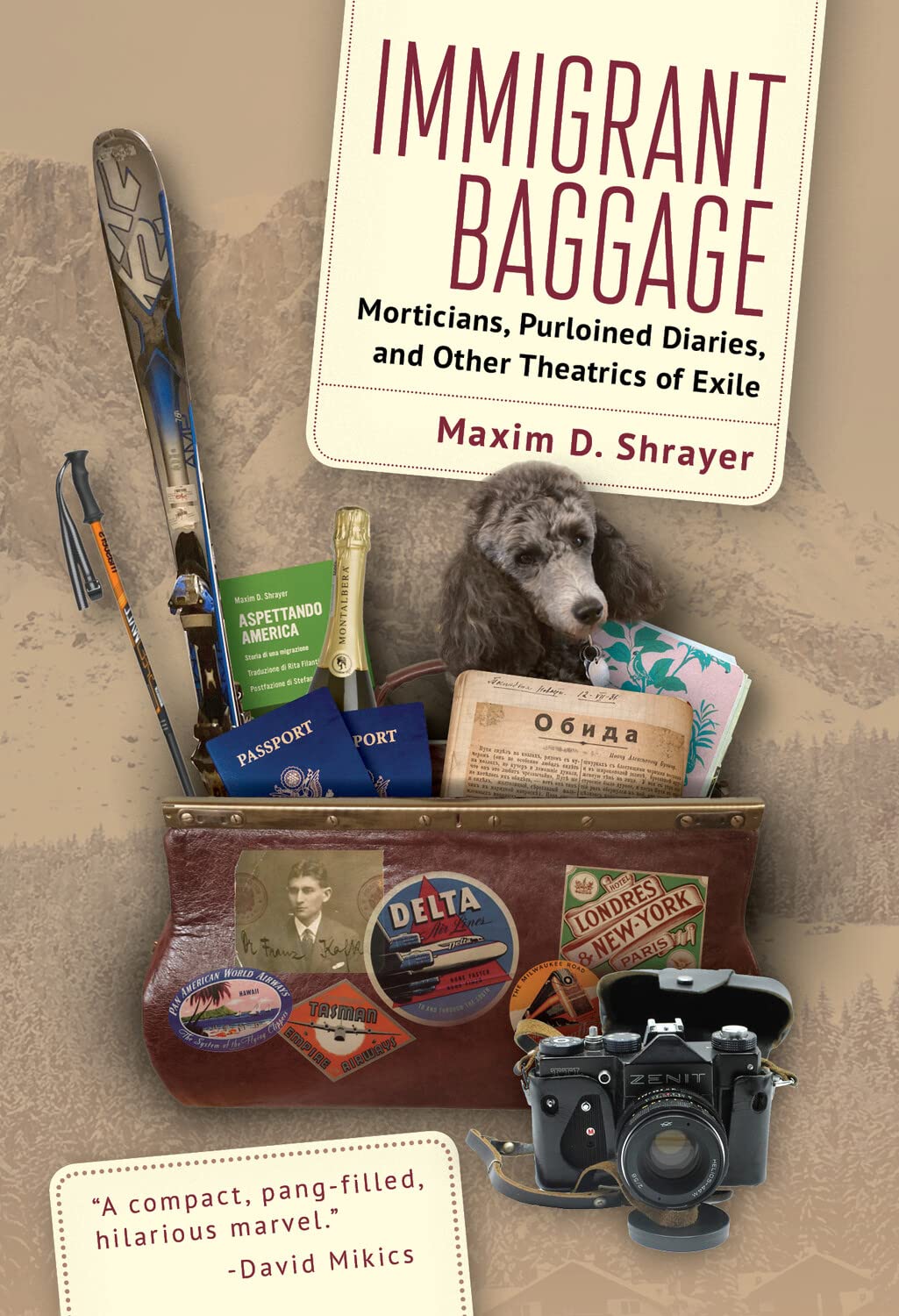

Coined in French for the purpose of describing a suitcase with two compartments, portmanteau connotes a dual purpose. The word kept coming to mind as I read Maxim D. Shrayer’s delightful literary memoir, Immigrant Baggage: Morticians, Purloined Diaries, and Other Theatrics of Exile. Admittedly, I am susceptible to suggestion. The recurrence of portmanteau is therefore likely due to the book’s cover, which features an old-fashioned valise—the genuine article—filled with sundry objects. Just to the left of this carryall’s centre, their top halves protruding, are two official identity documents. One is clearly labelled PASSPORT. Peeking out from behind it, the second leaves only PORT visible. As it happens, Port stands for many things. It means to carry, but it also designates an opening or a gateway to a city that is walled or guarded.

There is more that needs saying about the image of the travel bag—crammed with meaning, as it were—and its miscellany of items. First, the bag itself is an obvious metonym for both travel and displacement. The former we associate with the figure of the traveler/journeyer: someone driven by wanderlust and with sufficient freedom to roam the world. The latter is a trope for the immigrant/migrant, a person forced out of their home(land), and temporarily or permanently enduring statelessness or un-belonging to any place or community. Both figures—the intrepid wanderer and the migrant—are discernible in Shrayer’s book. This duality is reinforced by the other contents of the capacious valise decking the book’s cover.

Shrayer’s “baggage” holds a silver poodle (Shrayer’s own dog), a bottle of Montalbera champagne, and a vertically ensconced ski with ski pole—all of which surely point to stable and happy domesticity, material comfort and its rewards. However, other items in the bag serve as more ambiguous ‘signs,’ and speak of a peripatetic and fraught existence. For example, behind the ski is a book cover with the title Aspettando America. It’s a copy of the Italian translation of Shrayer’s literary memoir, Waiting for America: A Story of Emigration (2007), an instance of literary translingualism and translation. Both preoccupy Shrayer on a number of personal and professional levels, as I’ll explain below. What matters for now is that the translated memoir makes parts of Shrayer’s life story available to Italian-language readers. They can discover what it was like for Maxim and his parents to live through months of uncertainty in Italy, in the summer of 1987, while waiting for official permission to immigrate to America. Visas to the US were by no means guaranteed. At the time, the Shrayers, like thousands of other families from the former Soviet Union, remained in a limbo of statelessness.

Significantly, the interval in Italy was preceded by a far lengthier, considerably more difficult period of waiting in Moscow, the Shrayers’ native city. It took almost nine years for the Soviet government to grant the family permission to emigrate. For nearly a decade, Maxim and his parents lived as refuseniks (i.e., the rejected), also a translingual label and one that speaks of the legal casuistry commonly practiced by Soviet authorities.

In effect, the government punished its citizens for wanting to emigrate. Those who applied for permission to leave, the vast majority of whom were Jewish, were spitefully denied their exit papers, often for many years. Moreover, they were officially blacklisted, framed, for all intents and purposes, as ideological enemies of the state, and subjected to various forms of abuse. The more gifted and accomplished of the refuseniks, those with stellar careers in the arts or sciences, for example, generally faced the most severe repercussions. Many were demoted or lost their jobs altogether. Most were ostracized socially and professionally.

Exile and Injury

Soviet reprisals against the sons and daughters of the motherland who wished to relinquish their citizenship were injurious by design; they were intended to have an impact long after emigration. Ever since the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, writers, musicians, dancers, and visual artists fleeing the country underwent a form of erasure at home. Their work was either destroyed, taken out of circulation, or else publicly denigrated—“cancelled,” in today’s parlance. Once outside of Russia, such exiles were forced to start anew. Most were financially strapped, linguistically constrained, and socially isolated. To their adoptive societies, many of them became persons of little or no cultural consequence.

Among the objects in Shrayer’s carryall, one in particular alludes to the plight of writers in exile from the USSR. Given centre stage is a copy of a page clipped from Vladimir Nabokov’s story “Oбида”/“Obida.” The title can be translated from the Russian as “The Offense,” or “The Injury,” but Nabokov, ever the translingual punster, preferred “A Bad Day.” Published in 1931 in a daily Parisian Russian-language newspaper, this semi-autobiographical narrative is about one miserable day in the life of an adolescent boy, Peter Shishkov. Precocious and aloof, yet sensitive and vulnerable, the young man is rebuffed by his peers. The story, with its dedication to Ivan Bunin, evokes Russia’s pre-revolutionary, genteel past while hinting at the alienation felt by its author.

The Nabokovs were Russian aristocrats, forced to flee in 1919. Partly because of this, Vladimir couldn’t make a living as a writer until decades later, after he had begun writing in English. His first novel in English, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (also the first not to be published under his pen name, V. Sirin), came out in 1941, but it was only with the publication of Lolita in America in 1958, that V. N. received major recognition outside of the Russian-speaking émigré circles, as well as royalties that made him financially independent. Interestingly, and related in no small way to the playful arrangement of signifiers in Shrayer’s bag, is the central theme of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight. It revolves around the unknowability of the real Sebastian, a reclusive and enigmatic Russian-born author, aspects of whose life and identity in the West—in true Nobokovian fashion—elude his most earnest biographer. The novel entails a metafictional grappling with language and its limits, particularly the subjective and illusive nature of text/s that claim to be true to life.

The clipping of V. N.’s “A Bad Day,” its conspicuous placement in the valise especially, signal Shrayer’s abiding interest in Nabokov’s life and art. Along with other items, it connects Shrayer to the renowned novelist’s lifelong preoccupation with the functions of language and translation, or what he called “the queer world of verbal transmigration.” This formulation was of the émigré author’s own devising. Nabokov used it to commence an essay he penned for The New Republic, “The Art of Translation: On the Sins of Translation and the Great Russian Short Story” (1941). There is more that needs to be said about translation, the act of writing in an-other’s language, and its significance for Shrayer. For the moment, let me stress that the clipping of “A Bad Day” gives voice to the anguish shared by exiles (all of whom are forced to leave their native land) and refuseniks alike.

Nabokov’s story is meaningful to Shrayer on several levels, due in part to his own experience. The very act of submitting the request to emigrate from the USSR exposed applicants, especially in the 1980s, to spurious red tape. As a result, these refuseniks or ‘undesirables’—not wanted aboard, but inexplicably and cruelly prevented from leaving—were caught in a labyrinthine process of a type that Kafka’s admirers might appreciate. The chapter titled, “In the Net of Composer N.,” one of the six narratives in Immigrant Baggage, briefly describes the effects of “refusenikdom” on Shrayer’s family. The tale begins with events that transpired in Maleyevka, a village outside of Moscow and home to a retreat for Soviet authors and their families. First, however, Shrayer offers this glimpse of life on the margins:

My mom had already said goodbye to her beloved job as a professor of business English and interpreter. My father, too, had bid adieu to the Research Institute of Microbiology, where he had worked since the mid-1960s. My parents had placed their Soviet careers, quite successful for Jews who weren’t party members, on the execution block, except that instead of permission to leave, refusenikdom awaited us. For my father, that winter vacation at Maleyevka was also a farewell to his life as a Soviet writer. His official punishment just for the “attempt at exodus” (my father’s words) would be not only banishment from academic life but also expulsion from the Union of Soviet Writers, the derailment of three books, and public ostracism. (Immigrant Baggage 50)

Thus begins a narrative cleverly structured around a Nabokovian knot with a tinge of the Kafkaesque.

Shrayer displays a particularly deep regard for Nabokov in this chapter, but not just because Nabokov’s exile evokes in him a form of fellow feeling or solidarity with writers forced out of their cultural habitats. Here and throughout Immigrant Baggage, Shrayer overlays the more unpleasant experience of “refusenikdom,” with the positive outcomes of emigration. “In the Net of Composer N.” is witty and irreverent, and is as much a celebration of creative freedom from Soviet-style petty rivalries, political intrigues and cultural shackles (still in effect under Putin), as it is a tribute to Nabokov’s artistry and life-long passion for lepidoptery. In form and content, the story reminds readers that exile or immigration, and their attendant cultural and linguistic dislocations, are also a creative unmooring. Despite drawbacks, life in the West was formative for the young Nabokov and highly productive, enabling him to break free of his native country’s politics, as well as from the constraints of Russian realism (and later those of early modernism).

Shrayer, too, established himself as a poet, translator, and accomplished literary scholar after reaching the United States in 1987 (he is the author of numerous scholarly works, four memoirs, several books of literary fiction and nonfiction, and four collections of verse). Yet like Nabokov, Shrayer never entirely abandoned Russia or its great authors. Currently a professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies at Boston College, he continues to study Russia’s writers of the past and present. He even weaves the people and places he used to encounter during his annual sojourns in Russia, where he used to give readings or participate in literary conferences, into his narratives (such trips, and Shrayer’s participation in Russia’s cultural and academic life, ended with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). Immigrant Baggage, which combines the ‘realism’ of autobiography and travelogue with deft touches of scholarly inquiry, is therefore a portmanteau in more ways than one. The book functions as memoir and serves—concomitantly—to map part of 20th century’s literary history. Appropriately, the fifth and longest of the book’s chapters, “Yelets Women’s High School,” is a roundabout exploration of the legacy of the aforementioned Russian émigré author Ivan Bunin.

Bunin, also exiled after the Russian Revolution, lived in France, became a formidable anti-Bolshevik, and, according to Shrayer and other prominent scholars, was a major influence on Nabokov’s writing. “Yelets Women’s High School” begins with a flashback to Shrayer’s time as a student at Moscow University, and his youthful notion for an original stage adaptation of Bunin’s novella, Light Breathing (published in 1916 and later hailed as a masterpiece of Silver Age prose). The novella is about the seduction of a schoolgirl, Olga Meshcherskaya, by an older man, which leads to her murder by a jealous suitor. Yet what drives the plot of Shrayer’s narrative is not Bunin’s tragic heroine, or not exactly. It is the intriguing disclosure, by a young woman Shrayer is briefly acquainted with as a member of a theatre directors’ workshop, that Bunin himself was at one time similarly infatuated and involved with a school-aged girl from the local gentry in the south-central Russian city of Yelets, made famous for a time by its wealthy merchants.

At the centre of Bunin’s novella is the deceased girl’s diary, which recounts her seduction and its life-altering consequences. Shrayer’s narrative, always subtly alluding to elements in Light Breathing, ends with his visit to Yelets in the summer of 2019, and a somewhat unsettling, nighttime attempt to access the locked contents of a display cabinet, which stands in a building that at one time housed the local women’s high school. The cabinet, Shrayer believes, likely contains the 1886 diary of one Olga Yeletskaya, the very same girl purported to have been the model for the murdered heroine of Light Breathing.

An unapologetic hound of historical minutia, Shrayer gets close but ultimately fails to confirm Bunin’s alleged indiscretion. Yeletskaya’s enticing diary, then, and what it could have revealed apropos Light Breathing and Bunin’s later writing, remain for Shrayer and his readers provocatively out of reach. Hence, “Yelets Women’s High School” can be described as a quaint literary mystery wrapped in a deceptively mundane account of the author’s visit to Yelets, a city 400 km removed from Moscow, Russia’s capital. The city and its denizens, Shrayer also makes amply clear to his readers, haven’t yet entirely shed their laughter-inducing parochialism.

In “Yelets Women’s High School,” Shrayer self-consciously parallels the literary appositions both Nabokov and Bunin featured in their work: of Russia’s past and post-revolutionary present; and of life in a metropolis and the society and mores of small towns and villages. Shrayer makes certain to draw comic relief from some of the authors’ outdated aesthetics, along with their fictions’ pre-revolutionary, idealized settings, personages, and language. At the same time, he strips the ethos of a Communist state down to its unsightly pretensions, the cliched bromides and denunciations of Soviet- and Putin-era literary critics and cultural authorities (their atavistic anti-Semitism included). For instance, in “Yelets Women’s High School” a nettled response from Iosif Lopatkin, the director of the people’s theatre at Moscow State University, apropos Shrayer’s proposed theatrical adaptation of Light Breathing, is reproduced as follows:

Tossing a long grey lock off his forehead, Iosif Lopatkin turned to me, lenses of his gold-rimmed spectacles ablaze, and screamed out:

“Why in the world do you care so much about Bunin? The fascists stood at the gates of our motherland, and he sat in his villa in the Maritime Alps and wrote about naked arses.” (Immigrant Baggage, 100)

Light-handed satire of this type is found throughout Immigrant Baggage. Nor does its author abstain from making fun of his own pretensions and misconceptions.

The Kafkaesque

Shrayer is persistently upbeat, even appearing to take a perverse delight in relating problems of excruciating—one might add, of somewhat unnatural—complexity. His good-natured forbearance, as he moves from one misadventure to another, are hard to reconcile with the photo of Franz Kafka affixed in the form of a sticker to the bottom of the valise on the book’s cover. Yet the mingling of humour with contretemps that confound Shrayer over and over is not coincidental. The memoir’s final chapter, “A Return to Kafka,” is about another mind-bending impasse involving obturate, wearisome functionaries. Here, too, Shrayer is playful in a fashion that seems incongruous given the unmistakable reference to modern Prague’s herald of doom and despair.

Shrayer begins his account, “Return to Kafka,” with a conversation he had in 1989. He is speaking with Konstantin Kuzminsky, a poet and an anthologist of Russian avant-garde poetry, about authorial predispositions and aesthetics. Opinionated and assertive, the anthologist insists that there are fundamentally only two kinds of writers: “Kafkians” and “Rabelaisians.” Kafkians, he declares, are “cerebral, sickly, darkly shaded, depressing, sparsely worded.” By contrast, Rabelaisians are “exuberant, carnal, verbally inventive.” Key here is Kuzminsky’s conviction that Jewish creators are Kafkians on the whole. When Shrayer objects, pointing out that neither Chagall nor Babel were melancholy artists, Kuzminsky replies: “Those are exceptions” (132). Yet such exceptions tend to prove the rule, as Shrayer repeatedly demonstrates with his surfeit of “theatrics.”

In “A Return to Kafka,” we find—at last—Shrayer slyly accounting for the mood, if you will, that pervades all of Immigrant Baggage: a light-heartedness at variance with accounts of obstructing bureaucrats and administrative tangles that are nearly surreal in their intractability. Shrayer is aiming, it appears, not just to disprove Kuzminsky’s charge that Kafka is humourless, but to debunk his entire aesthetic theory of categorical opposites. Accordingly, in Immigrant Baggage, Kafka-isms are nearly always leavened by a Chagallian weightlessness, a whimsical dreamworld Chagall used to depict the embattled Jewry of Eastern European shtetls as escaping/transcending the gravity of their otherwise somber circumstances (this might account for a number of whimsical plot twists in Immigrant Baggage).

Additionally, Shrayer plays off Kuzminsky’s strident pronouncements by reflecting on his own connection to Kafka:

For years I appreciated Kafka but kept my distance. I taught him on occasion, and I even published a bit on Nabokov’s visit to Prague and his begrudgingly acknowledged debt to Kafka. But Kafka wasn’t a writer I loved to read for pleasure. And the ex-Soviet in me never got into the habit of throwing the term “Kafkaesque” left and right‚ like some red badge of confusion.” (132)

His stated reservation notwithstanding, Shrayer’s reference to the “Kafkaesque”—in effect, to Kafka’s paradigmatic, surreal fiction, which doubles as a critique of modernity—is significant to the overall scheme of Immigrant Baggage (its many bureaucratic impediments especially). Moreover, we see that Shrayer also underscores the influence of the Jewish writer from Prague on Nabokov. Here, then, is where a reviewer must take a slightly more bookish view of certain lines of descent despite the author’s efforts not to overwhelm more causal readers with the minutiae of literary history.

Literary influence isn’t a trivial matter for Shrayer—not in this book, and certainly not in his scholarly projects. Thus, the literary relationships or affinities he references in the above passage extend beyond what can be said of Kafka’s wit and literary temperament. One must also take stock of Kafka’s and Nabokov’s consummate deployments of signs and symbols. Kafka is an acknowledged master practitioner. The same has been said of Nabokov. Shrayer, for his part, has craftily enacted a homage to both, using a portmanteau filled to the brim with signifying tokens to decorate his book’s cover—referentially, if not reverentially, outfitted with an iconic photo of Kafka’s own travel document.

Yet more pertinent still is Shrayer’s scholarly work, The World of Nabokov’s Stories, about which literary critic David Rampton writes the following: “The second chapter is…[an] account of how various signifying systems generate meaning in these stories (including devices as subtle as the repetition of phonemes)…[Additionally, it provides] analysis of minute particulars of translation and how they affect a reader’s understanding of these stories” (Rampton 708). Rampton’s review is a helpful reminder of what else matters enormously to Shrayer about Nabokov and Kafka: the difficulties they faced due to writing in a lingua franca that wasn’t entirely their own. This is the aspect of Immigrant Baggage to which I alluded at the start of the review. In his own words, Shrayer, an immigrant, “a translingual subject,” is likewise labouring to surmount, “borders—or boundaries—includ[ing] those of languages, cultures, and countries, some of them invisible while others still guarded with silences or even barbed wires” (Immigrant Baggage, 18-19).

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s seminal study, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (1986), conceptualized minor literature, the creative work of a “translingual subject” (who was Jewish and Czech/Bohemian, but educated in German), as agitating against the walls guarding the space of established literature while making room for new categories and genres. In his foreword to Deleuze and Guattari’s book, Réda Bensmaïa asserts that “[t]he concept of minor literature permits a reversal: instead of Kafka’s work being related to some preexistent category or literary genre, it will henceforth serve as a rallying point or model for certain texts and ‘bi-lingual’ writing practices that, until now, had to pass through a long purgatory before even being read, much less recognized” (xiv). Such practices are always in the process of assailing or provoking the dominant language, culture, and preferred literary traditions of the social majority.

Kafka was barely published during his lifetime. As for Nabokov, it took him two decades after leaving Russia to publish a novel in English. We might surmise that his investment in translation as practice and theory (one might even call it an obsession) was in no small way a product of displacement, of struggling to make his work understood as a stranger in another man’s land and language.

“In the not so recent past,” Shrayer states in “Translingual Adventures,” his foreword to Immgirant Baggage, “translingual writers used to be all alone, artistically homeless, culturally stateless” (15). Among the examples he gives of lonely authors is Samuel Beckett, “the Irish literary genius who spent much of his adult life in France and translated most of his French works into English” (16). Happily, those who left the USSR for the New World now find themselves in a “translingual neighbourhood,” part of a creative community, “both in their own eyes and in the eyes of the American and Canadian cultural mainstream” (16-17). Yet the challenges of writing transligually persist, especially when these efforts require self-translation.

For immigrants or exiles, finding themselves on the margins of a dominant culture, language, and literature, learning to write in a new language is the ultimate ‘transmigration’ or rebirth. The writer spends a lifetime recalling and reconstituting their previous self and the world—culture and language—that shaped it. The effort is quixotic. The old self can never be re-presented, as most immigrants from the Soviet Union can attest. Those who settled around the Eastern Seabord of the US, or in Ontario, Canada, would no doubt say their past selves can’t ever be fully re-recreated. Glimpses of an old self persist, however. Perhaps this is why even after 37 years of living in America, Shrayer concedes that he, like any other immigrant, must fall back on dreams for visions of his previous life. In dreams, borders are easier to cross. It is also in dreams where an immigrant writer has what Shrayer describes as “a deeper access to mechanism of culture production—mechanisms that probably impact translingual writers most profoundly by revealing the hidden texture of exile.”

For these and other reasons touched on in the essay, Immigrant Fiction is not merely a pleasure to read; it is an important work. It counts, to draw on Réda Bensmaïa’s description, among the works that serve as a “rallying point…for certain texts and ‘bi-lingual’ writing practices” that are finally emerging from the peripheries of American and Canadian literatures.

References

Anisimov, Kirill. “Paschal motifs in Ivan Bunin’s “Light Breathing.’” Vestnik

Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Filologiya, vol. 44, no. 6, December 2016. 10.17223/19986645/44/6

Benjamin, Walter. “Franz Kafka.” Illuminations. New York, Schocken Books, 1969. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Kafka : Toward a Minor Literature. University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Larson, K. Maya. “Nabokov’s ‘Diabolical Task’: Translation as Capture and Becoming-Butterfly.” Deleuze and Guattari Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, 2020, pp. 585–603, https://doi.org/10.3366/dlgs.2020.0419.

Nabokov, Vladimir. “The Art of Translation: On the Sins of Translation and The Great Russian Short Story.” The New Republic, August 4, 1941. https://newrepublic.com/article/62610/the-art-translation

—. “Problems of Translation: Onegin in English,” Partisan Review, no. 22 (1955): 512.

Rampton, David. “Review” of The World of Nabokov’s Stories by Maxim D. Shrayer.” Slavic Review, vol. 59, no. 3, Oct. 2000, pp. 707–708, doi:10.2307/2697406.

Rosenberg, Victor. “Refugee Status for Soviet Jewish Immigrants to the United States,” Touro Law Review, Vol. 19: No. 2 (Article 22): 419-450 . https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol19/iss2/22:

Shrayer, Maxim D. “Anti-Zionist Committees of the American Public: The war in Israel and the legacy of Jewish political apostasy.” Sapir: A Quarterly Journal of Ideas for a Thriving Jewish Future, October 2023-February 2024 (Special Edition: War in Israel). https://sapirjournal.org/war-inisrael/2023/12/anti-zionist-committees-of-the-american-public/

—. Immigrant Baggage: Morticians, Purloined Diaries, and Other Theatrics of Exile. Cherry —-. A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas. Cherry Orchard Books, 2019.

—. With or Without You: The Prospect for Today’s Jews in Russia. Academic Studies Press, 2017.

—. Leaving Russia : A Jewish Story. First Edition., Syracuse University Press, 2013.

—. Yom Kippur in Amsterdam: Stories. Syracuse University Press, 2012

—. Waiting for America : A Story of Emigration. 1st ed., Syracuse University Press, 2007.

—. The World of Nabokov’s Stories. Literary Modernism Series. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999.

—. “Vladimir Nabokov and Ivan Bunin: A Reconstruction.” Russian Literature, vol. 43, no. 3, 1998, pp. 339–411, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3479(98)80006-9.

Olga Stein

Olga Stein earned a PhD in English from York University, and is a university and college instructor. Stein teaches courses in communications, humanities and social sciences at Centennial College and York U. She has also taught writing, modern and contemporary Canadian and American literature, and a gender studies course called “Love: Historical and Philosophical Perspectives.”

Stein’s research and writing focuses on the sociology of literature, popular culture, and cultural institutions. As chief editor of the literary review magazine, Books in Canada, she contributed more than 150 book reviews and essays, 60 editorials, and numerous interviews. For the past three years she has been the non-fiction editor for WordCity Literary Journal, a multi-genre, global online literary journal to which Stein contributes critical essays, editorials, interviews, and poems. She hopes to publish her collection of essays as Reflections on the (Re)Current Moment. Stein was shortlisted for the 2023 annual Fence Magazine short fiction competition. She recently also completed her first collection of poetry, Love Songs: Prayers to gods, not men. Her poetry has appeared in WordCity, Atunispoety.com, and several international poetry anthologies.