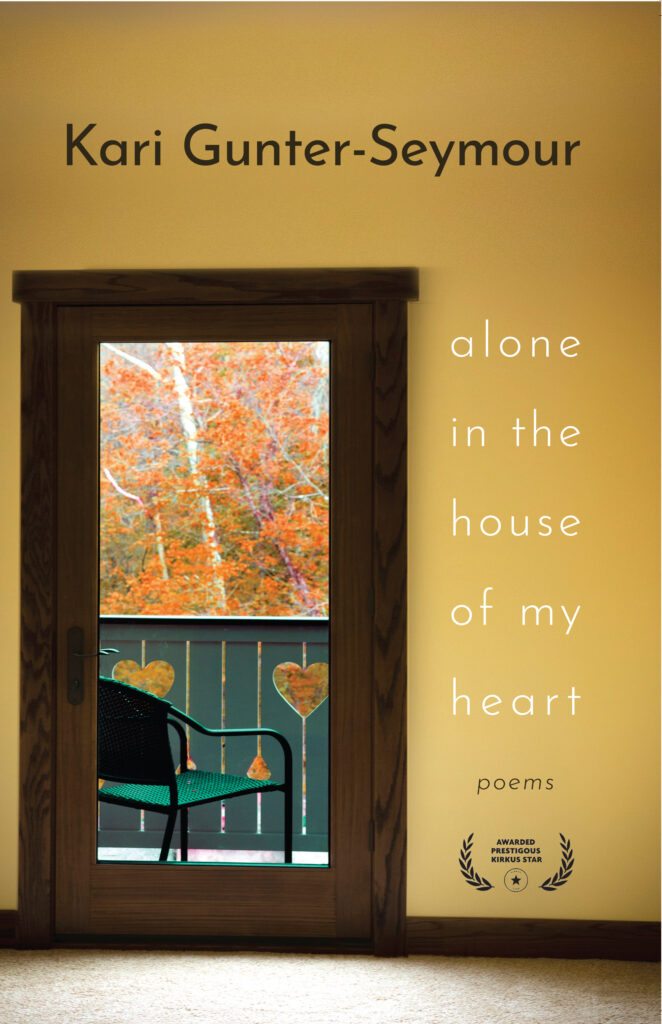

“For my people–steeped in survival and hallelujah.” The dedication page in Kari Gunter-Seymour’s third book of poetry reads like a one-line poem unto itself. Gunter-Seymour has lived all her life in southeastern Ohio, and the dedication springs from nine generations of ancestors as well as the whole community of peoples rooted at the northern foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Each poem in this deeply felt collection has a strong sense of place and at the same time tells an intimate story. Take, for example, these stanzas from the poem “To No One in Particular,”

“For my people–steeped in survival and hallelujah.” The dedication page in Kari Gunter-Seymour’s third book of poetry reads like a one-line poem unto itself. Gunter-Seymour has lived all her life in southeastern Ohio, and the dedication springs from nine generations of ancestors as well as the whole community of peoples rooted at the northern foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Each poem in this deeply felt collection has a strong sense of place and at the same time tells an intimate story. Take, for example, these stanzas from the poem “To No One in Particular,”

I take solace in considering the age

of this valley, the way water

left its mark on Appalachia,

long before Peabody sunk a shaft,

Chevron augured the shale, or ODOT

dynamited roadways through steep rock.

I grew up in a house where canned

fruit cocktail was considered a treat.

My sister and I fought over who got

to eat the fake cherries, standouts in the can,

though tasting exactly like every other

tired piece of fruit floating in the heavy syrup.

But it was store-bought, like city folks’,

and we were too gullible to understand

the corruption in the concept, our mother’s

home-canned harvests superior in every way.

I cringe when I think of how we shamed her.

So much here depends upon

a green corn stalk, a patched barn roof,

weather, the Lord, community.

We’ve rarely been offered a hand

that didn’t destroy.

I asked Kari what she most wanted to share about her home region—what did she hope people would remember and better understand? “The old ways. Caring for the land, being good neighbors, good people, being honorable. Having the honor of resting on such beautiful land and the importance of being kind, including to animals.” She is keenly aware that because her ancestors fought through hardships, she is afforded the luxury of writing about them. And how proud of her they would be —Gunter-Seymour is currently Ohio’s Poet Laureate. Speaking of her connection to the land, she told me, “All my people, up until my grandparents, raised their own food. I feel blessed to have been included and to have observed them.” She keeps a garden with the help of her son but earned her living teaching communications at Ohio University. Amazingly, her first poems were published only nine years ago; her formal education is in graphic design and commercial photography. As a reader, I have a sense that her life as a poet is a culmination of experiences that seem to be presenting themselves all at once as things that must be written about to be fully and completely lived.

One of the recurring themes I noticed in Alone in the House of My Heart is change: changes in place, seasons, generations, and family composition. Lines that I felt capture this perfectly are, “What is history anyway, / but a conversation we’re born into/without context” (from “To Those Messaging Me After My Mother’s Passing”). This poem and others struggle with the problem of understanding ourselves, our origins, and the people with whom we live our lives. They surface the grief and anger that necessarily show up together at times. I asked Kari why she thinks poetry works to cope with powerful feelings:

“I write my way through my pain and grief and my anger. Poetry is healing. Reading and listening–it’s like being anointed. When we lift up our words we get out of our heads; it gives relief. Our heads are where the bad stuff lives; it can be so negative in there. Anger and grief can be constant if you let them be. I write until I can finally make sense of it.”

This made me think of a very arresting line – the introduction to part 4 in the book, which reads: “Mostly, a cage is air.” I had never thought of a cage that way. Isn’t the wire of a cage the only thing that matters? But Kari said that to her it means we don’t let the wire take us so far down that we don’t get up again. “I go back to the ancestors for that; if they had laid down even once I might not be here now. I’m in the cage but I’ll seek out the air. Some days I stare at the bars–that’s grief and that is OK–but make sure you get good full breaths of air as well.”

Speaking of clean air, Gunter-Seymour’s mother passed away during COVID lockdown, when breathing the same air as other people became a serious matter. The poem “Rare Birds” is a tribute to her mother. Although COVID was not the cause of death, she was living in a nursing care facility due to her dementia, and entering her room required an involved sequence of washing, gowning, gloving, and masking. After six weeks without contact, Kari was allowed in. Her mother asked, “Where have you been?” “I’ve been out reading my poetry like I do,” she responded. “She was very proud of me.” In “Rare Birds,” the poet plants a tree to welcome “rare Kirtland warblers, who / are picky, require jack pines / rooted in Grayling sand.” This is in honor of her mother, who was “colorful, flighty, could trill / a rich, clear aria. / She never left the house without / her signature kohled eyelids / and some form of feather-crested frock.” She was a “petunia among the ragweed,” Kari said, and the poem is one she would have approved of. On the other hand, “Some of the poems are not as forgiving because they are about my youth.” Her mother’s bipolar disorder could be a source of hurt, as was the case when she proposed that Kari, at thirteen, lose five pounds to earn a Barbie. This instance appears in the poem “Hella Barbie 1968,” which is about her mother’s perhaps misguided efforts to steer her in certain directions, life’s pressures and disappointments, and how we become familiar with them too soon. I loved the poet’s response, however,

…To insistordinary things be somehow more–

a brittle leaf laced in snow,

the sugary smell of clover-filled pastures,

my mother’s voice, twanged and weedy,

calling, Don’t be late for supper!

Lose weight but don’t be late for supper. What a bind! Another theme is the demands and judgements that women face, particularly Appalachian women. In “An Appalachian Woman’s Guide to Beer Drinking,” she hands a longnecked bottle to women who have offered “bits of your body, your land, to earn so little / as a pine-splint stool at their stars-and-stripes table.” This poem was written after the hearings to appoint Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, a detail I found deliciously hilarious.

Other poems are part lament, part love letter to the land. I can’t do them all justice here, but in closing I asked Kari what she’s currently working on and what comes next. She has a fourth book of poetry titled “Dirt Songs” coming out in 2024 from EastOver Press. It honors the women she grew up with in Amesville, Ohio who were not offered the same opportunities for education that she managed to acquire for herself. New poems she’s working on now are about her sister who died unexpectedly a year ago. More working out of grief and pain. But you must, Kari said, “write it, because if you hold onto it, it changes you.” Lucky for her readers, she writes through it all.

Emily Updegraff

Emily is a Reviews Editor at Great Lakes Review.