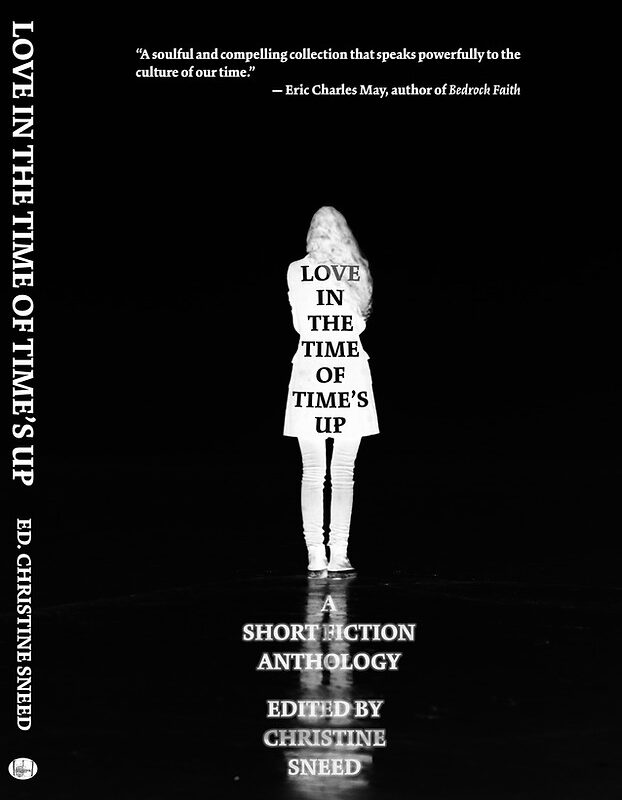

Love in the Time of Time’s Up is a new anthology that takes an (unfortunately) timeless topic – sexual exploitation – through seventeen unpredictable, enraging, but also compassionate and reflective stories. Christine Sneed is the author of six previous books and teaches writing at Northwestern University. This anthology, published in October 2022 by Tortoise Books in Chicago, is her first venture as a book editor. I met with Christine to learn more about how this endlessly interesting book came to be.

Love in the Time of Time’s Up is a new anthology that takes an (unfortunately) timeless topic – sexual exploitation – through seventeen unpredictable, enraging, but also compassionate and reflective stories. Christine Sneed is the author of six previous books and teaches writing at Northwestern University. This anthology, published in October 2022 by Tortoise Books in Chicago, is her first venture as a book editor. I met with Christine to learn more about how this endlessly interesting book came to be.

As the title implies, the stories relate in one way or another to the problems of harassment, assault, and imbalances of power in relationships. That said, each story is utterly unique, and even as I found myself looking for the “bad guy” as I read, the identity of the person with malicious or selfish intent is not static, nor is it always straightforward to assign such blame. Instead, these are stories that will make readers think in new ways about desire, motivation, and the cultural norms in which they play out.

The stories cover so much territory that I wondered if, as an editor, Christine began with a set of pieces that she wanted to include and proposed an anthology around them. But in fact, it was the reverse. She notes, “I went out and solicited the stories. I queried a number of female writers, most of whom I knew personally. Some of the stories were already published, and a few I had not read before they came in. I knew the writers so I knew they would send good work. The whole thing was a happy experiment.” She wrote the book proposal in January 2020, with the intent that her agent would place it with a publisher, but the project stalled with the pandemic and instead sold it directly to Tortoise Books.

I was curious whether the title is a direct reference to the nonprofit organization Time’s Up, which focuses on sexual assault and discrimination at work. Christine said it wasn’t quite that, but rather, it just felt like the right title. She has a background in poetry and often begins her poems with a title; in this case, she began an anthology that way. Still, the oblique reference to workplace assault dovetails nicely with the opening story by Karen E. Bender, in which assault occurs at a workplace. As someone who has had annual sexual harassment training at work for many years, I sometimes wonder about the effectiveness of such training—does it make an impact on the people who need it most? Does focusing on behavior at work affect behavior outside of work? These questions are outside the scope of these short stories, but in our conversation, Christine noted that in her first job, in the early 90s, “The support staff was all women—working at cubicles—and the people in the offices, for the most part, were men.” That has started to change, but power differentials die hard.

In the story “A Good Plan” by Joan Frank, a woman observes a man and a woman on a train. Based on a few physical details and words they exchange, the observing woman makes some unflattering conclusions about the couple, particularly around the power dynamics of their relationship.— I admit that I’ve looked at people like that, judging, sizing them up against the parts of my life that feel well put together at the time. The last line of the story stuck with me: “The two step [off the train] into the world that made them.” It begs the question of how toxic inequalities develop and suggests that perhaps they always will in an imperfect world.

In the story “Lil” by Melissa Fraterrigo, the person leveraging power is a woman with a disability who tries to make the teenage girl she hired to help her with household tasks hook up with a man, apparently for her own entertainment. To me, it was one of the most disturbing stories. I often think of bad behavior in men as being socialized into them by patriarchal culture, a culture that tells them they’re entitled to the attention and availability of women. “Lil” is one of the stories that complicates this line of thinking, and I asked Christine what she believes makes people behave with entitlement toward others. “I’m sure there are quite a few reasons. To my mind, a lot has to do with wanting to be the one with the most power. It’s fear-based. It’s about control and about power.” We agreed that women are not necessarily better bosses in terms of the respect and mentoring that they offer their employees. “Unless you’re a very special person, it’s likely you will abuse your power.” Sometimes people do so in ways they are unaware of, as in the satirical piece, “The Sacrament of Brett,” where Roberta Montgomery brilliantly shows the malignant obliviousness that one man nurtures throughout his life—conveniently blind to his own entitlement.

Given the many real-life stories of abuse and assault that came out in the wake of Me Too, I asked Christine to comment on the way fiction can contribute to the public discussion of these issues. “My thought was that with journalism and memoir, it’s different in that you only have access to one specific person’s point of view, but fiction allows us more access to someone’s interior life. It’s a humanistic endeavor to make people more responsive. To paraphrase Ian McEwan, we read fiction to understand what it’s like to be another person. Fiction takes us out of ourselves, it’s one of the only real tools for giving access to another’s consciousness.”

Humor is another effective means of getting people to see things from a new point of view. The funniest story in the book, “Dudes in Theory” by Elizabeth Crane, is a series of responses to men on a dating app and it made me smile and wince as it poked fun at the standards men hold for women but from which they hold themselves exempt. Christine agreed, “Humor is important to make life bearable, especially in difficult times.” She recalled an episode of the NPR podcast Hidden Brain reporting on research that says a lot of Americans stop laughing at age 23—shortly after they enter the workforce. “I write humor, so I usually laugh every day,” she said. “I think this explains a lot, i.e. that people stop laughing when they enter the workforce. Not all societies have the suicide and addiction rates we have—I do think they laugh more.” A few well-placed doses of humor make what could otherwise be a heavy read seem not just bearable but enjoyable.

Finally, I asked Christine if this is a political book—does it make a statement or incite advocacy? “Not really,” she answered. “I want people to think. I want them to enjoy it, and I want people to read these stories and think, ‘This is a lot more complicated than it appears to be.’ I’m interested in this book helping people enlarge their perspective and empathy for others. I’m not trying to be prescriptive with this book, but I do hope we will be more nuanced in our thinking about gender dynamics.”

As I was writing this review, yet another news article appeared on my phone about sexual harassment and abuses of power. It’s depressing, and it feels endless. Why should we read fictionalized versions of this kind of thing when there’s more than enough of it in real life? In other words, why read fiction at all? “It takes us out of ourselves,” Christine said. “We should all be required to read at least two works of fiction a month. I’m certain we’d be a different country if we did.” I agree. Stories have the power to change minds if only because they can put you in the place of another person, however briefly, however uncomfortably or reluctantly. These stories did that for me from some unexpected vantage points, making me think about character and motivation in new ways. That experience, above all, is why I read.

To learn more about Christine’s work, visit her website. Her upcoming short story collection, Direct Sunlight, will be published in June 2023 by Northwestern University Press.

Emily Updegraff

Emily is a Reviews Editor at Great Lakes Review.