French author Albert Camus (1913-1960) was one of those freak oddities that randomly come along and enrapture us – a celebrity philosopher. Unlike professional philosophers such as, say, Wittgenstein or Heidegger, whose language was arithmetical and whose logic was chilly and incisive, Camus’s prose was elegant, incantative, charming; and his reasoning, though usually rigorous, always preached humane action in an indifferent universe. In his works he came across as deep and ponderous, but also honest and well-intentioned, which is likely why people who don’t normally browse the Philosophy shelves of bookstores have embraced and loved him for decades. Everything Camus said or wrote—he was a master of the arch remark—seemed to make sense. (In my tattered paperback copy of The Rebel, acquired during college, nearly every page is a furrowed field of underlined phrases.) His voice, whether in novels like The Stranger or The Plague or in essayistic works like The Myth of Sisyphus, conveyed an edifying intimacy, as if he were whispering hard truths into our ear.

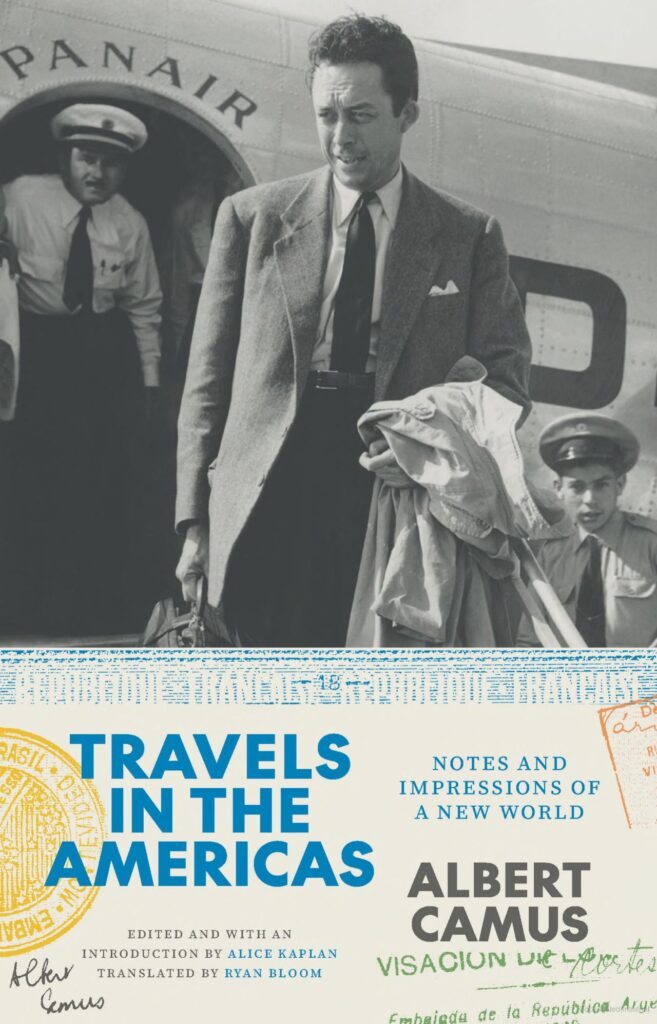

Writers probably produce nothing more intimate than their own private journals, where they are free to record their observations bluntly, without spitshining their prose or fretting over the wounded feelings of their targets. To read a writer’s journals is to scrutinize the writer at proximity, to see the writer’s mind as a dermatologist, or an undertaker, might see the flesh. So it is that the world owes a debt of gratitude to the University of Chicago Press, which has just published Ryan Bloom’s new translation of the journals Camus kept during brief visits to North America in 1946 and to South America in 1949. In these journals, published under Camus’s name and titled Travels in the Americas, we get an up-close glimpse of a writer surfing his first wave of international fame. We see Camus, committed to a speaking tour, suffering the travails of travel, eager to see what the New World is all about after witnessing the destruction of Old Europe in World War II. We see him dreading the necessity of meeting people, giving public lectures, sitting for interviews, and dealing with punctuality-minded hosts, often while he was ill. We see Camus benignly observing others’ behavior, appraising women, sizing up Americans, examining the Bowery, commenting on pet shops, libraries, and funeral homes, discovering Brazilians’ love of soccer. We see his reaction to rioting in Santiago, Chile, to race relations in New York, to the isolation of the Adirondacks and the beauty of Quebec. We see his almost comical hatred of neon lights, his distaste for any formal occasion, his incredulity at American wealth. In the journal entries from his 1946 visit, we see him working on his next novel, The Plague. We see a mind spinning like a perpetual motion machine.

When Camus arrived in New York in March 1946, he was virtually unknown to Americans. Those who had heard of him knew him as the leading editorial writer for Combat, the newspaper of the French Resistance. His wartime work had given him a sexy cachet accessorized by his good looks and a Humphrey Bogart sartorial style. The following months would amplify his glamor. The first English edition of his novel, The Stranger, was launched during his visit to New York. Publication of The Plague followed in 1947, and reader enthusiasm pushed it onto the bestseller list. When Camus arrived in South America in 1949, his star was ascending. He was beginning to experience the weight of international fame and celebrity, the demands for his time, the blinding glare of paparazzi flashbulbs. Camus’s journal entry for Aug. 10, 1949, captures the flavor of his trip:

The welcome given by the French officials in Montevideo lacks warmth. The dates for my talks have already been changed several times. Though I had nothing to do with it. They even neglected to reserve a room for me. I end up in a sort of comfortless storage room — where, all the same, I feel better than in the company of my forced hosts. It takes me a while to fall asleep, tossing and turning, focusing my willpower on not falling to pieces before the end of the trip.

Forced to admit to myself that, for the first time in my life, I’m in the midst of a psychological meltdown. That stable poise that’s withstood everything else has now collapsed, despite all my effort. Murky waters inside me, hazy shapes passing in them, sapping all my energy. This depression is hell, so to speak. If the people welcoming me here could only feel the effort I’m making just to appear normal, they’d at least make an effort to smile.

The book is full of such entries, a tangle of logistics enmeshed with angst and illness, melancholy and exhaustion. And always the demands of the (Sisyphean!) speaking schedule. Fortunately, there is something interesting or descriptive on every page, so the reader is never overwhelmed by Camus’s burdens. For instance, his encounter with roller skating on 52nd Street in New York: “A huge velodrome covered in red velvet and dust. In a rectangular box perched close beneath the ceiling, an old woman plays a most eclectic mix of tunes on a pipe organ. Hundreds of sailors, of girls dressed for the occasion in jumpsuits, pass from arm to arm in an infernal racket of metal wheels and pipe organ.” And from his South American trip: “Dinner at Suzannah Soca’s. A crowd of society women who, after a third whisky, become a little much. A couple of them literally offer themselves to me – but that’s not such a compliment.”

But as entertaining as Camus’s observations are, much credit for the book’s excellence should go to the many annotations provided by editor Alice Kaplan and translator Bloom. Their explanations are never intrusive, always welcome, appearing as footnotes at the bottom of pages like little gifts. Along with Kaplan’s scene-setting introduction, they provide rich context for much of what Camus encounters and writes. Kaplan is the Sterling Professor of French at Yale University, the coauthor of States of Plague (about reading The Plague during the Covid crisis), and author of Looking for ‘The Stranger,’ among other books, all published by the University of Chicago Press. Bloom is the translator of Camus’s Notebooks 1951-1959. In short, Kaplan and Bloom really know their subject. The introduction and the annotations are like perfectly placed windowpanes in a stone wall, bringing light to Camus’s more inscrutable remarks and to the things he left unsaid.

Some examples: In his journals, Camus refers to people mostly by a single initial; through their sleuthing and scholarship, Kaplan and Bloom identify many of the people he meets, including Camus’s cabinmate on the SS Oregon, which carried him to New York in 1946. Kaplan also notes that Camus was accompanied in New York and on the road by Patricia Blake, a student intern at Vogue whom he met after one of his lectures. She is never mentioned in the journals. Kaplan informs us in her introduction that, when he set sail for South America in 1949, Camus had renewed his love affair with the Spanish actress Maria Casares, a fact that helps explain his fretfulness over the lack of mail. Kaplan also cited correspondence between Camus and Casares indicating the two had vowed to exchange journals once they reunited, giving readers of Travels in the Americas a romantic lens through which to view his 1949 journal entries: when he wrote them, he knew she would read them. Kaplan also locates Camus’s travel within post-war geopolitics: Camus was an “official cultural representative of the French government” during both trips, and his visits were intended to help France “erase the scourge of Vichy” and “promote French language and culture in North and South America.”

Camus’s American journals were published in French by Gallimard in 1978, and in English translation in 1987 (translated by Hugo Levick, published by Marlowe & Company). The 1987 English translation, titled American Journals, provided almost none of the context that Kaplan and Bloom lavish on readers. Additionally, and unlike the earlier book, the Kaplan and Bloom edition includes many documents and images – the Cecil Beaton photograph of Camus for Vogue is fun and spooky – as well as a New York Post article on Camus’s visit and a “Talk of the Town” column from the New Yorker. While Camus’s journal entries detail how he saw Americans, these journalism pieces hold up a mirror to Camus, giving us the American press’s view of him.

Finally, Bloom’s translation is a model of tight writing. Though my French isn’t good enough to opine on Bloom’s faithfulness to the original even if I had a copy of it in front of me (I don’t), it reads briskly, as we would expect journal entries to read, and precisely, as we would expect of anything penned by Camus. It seems to me that Bloom has gotten something wonderfully right, marrying precision to concision. Below, chosen randomly, are samples of Bloom’s translation, followed by the earlier, Levick versions:

Bloom: “A stroll to Staten Island with Chiaromonte and Abel. On the way back, in Lower Manhattan, immense geological excavations between tightly packed skyscrapers. As we walk past, the feeling of something prehistoric overtakes us. We have dinner in China Town. For the first time, I’m able to breathe easy, finding real life there, teeming and steady, just as I like it.”

Levick: “A trip to Staten Island with Chiaromonte and Abel. On the way back, in lower Manhattan, an immense geological dig between skyscrapers which stand very close to one another; we advance, overwhelmed by a feeling of something prehistoric. We eat in Chinatown. And I breathe for the first time in a place where I feel the expansive but orderly life that I truly love.”

Bloom: “In Marseille, scorching heat and a wind strong enough to carve your face.”

Levick: “In Marseille, torrid heat and, at the same time, a wind that’ll blow your head off.”

Bloom: “I return totally worn out, tired of the human face.”

Levick: “I return to the hotel drained and exhausted, tired of human faces.

At 152 pages, Travels in the Americas is a small, beautiful gem, worthy of a large readership.

Rex Bowman

Born in Virginia and educated in small, public libraries across the United States, Rex is a translator and writer who now lives in St. Clair, Michigan, a temptingly short swim away from Canada. He has a sweet tooth for witty memoirs and wise essays and also loves to read literary nonfiction and travel yarns that emphasize people over landscape. As for fiction, his tastes are violently miscellaneous, but his favorite books have at least one of three things: unforgettable characters, fresh plots, or electric prose. He enjoys reading multiple translations of the same novel, and he relishes almost anything that isn’t ashamed to be fun (think Stella Gibbons, Richard Brautigan, Mario Vargas Llosa, Elif Batuman). Rex’s work has appeared in various literary journals, including Parhelion, Smart Set, Literary Heist, and Literary Yard. He is the author or co-author of several books, most recently Almost Hemingway: The Adventures of Negley Farson, Foreign Correspondent.