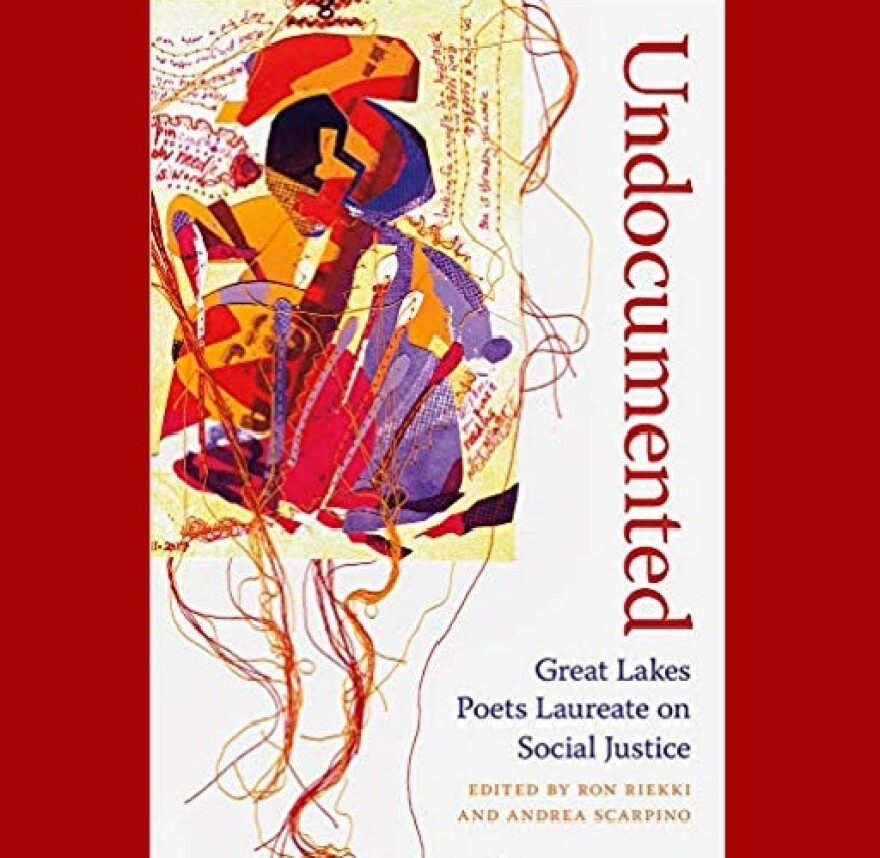

Ron Riekki and Andrea Scarpino have compiled an unprecedented collection of poetry in Undocumented: Great Lakes Poets Laureate on Social Justice (Michigan State University Press). While the collection is composed of poetry from only poets laureate spanning the Great Lakes, do not let the regionality fool you—the breadth and diversity of both the poetry and the poets cannot be overstated. The collection includes poets laureate of towns, cities, counties, and countries, who identify as white, cis, BIPOC, and LGBTQ, and who write about race, class, poverty, the environment, and war. Undocumented is likely the most diverse collection of poetry representing the Great Lakes region ever assembled. Most importantly, Undocumented not only showcases the prowess of poetry from the region but, more importantly, demonstrates, at the very least, the necessity of Great Lakes poetry to ongoing dialogue and much-needed reform surrounding human rights, equality, equity, inclusion, social justice, and environmentalism in the United States, Canada, and abroad.

Ron Riekki and Andrea Scarpino have compiled an unprecedented collection of poetry in Undocumented: Great Lakes Poets Laureate on Social Justice (Michigan State University Press). While the collection is composed of poetry from only poets laureate spanning the Great Lakes, do not let the regionality fool you—the breadth and diversity of both the poetry and the poets cannot be overstated. The collection includes poets laureate of towns, cities, counties, and countries, who identify as white, cis, BIPOC, and LGBTQ, and who write about race, class, poverty, the environment, and war. Undocumented is likely the most diverse collection of poetry representing the Great Lakes region ever assembled. Most importantly, Undocumented not only showcases the prowess of poetry from the region but, more importantly, demonstrates, at the very least, the necessity of Great Lakes poetry to ongoing dialogue and much-needed reform surrounding human rights, equality, equity, inclusion, social justice, and environmentalism in the United States, Canada, and abroad.

The collection is divided into ten sections, aptly named after the Southern Poverty Law Center’s (SPLC) “Ten Ways to Fight Hate: A Community Response Guide.” Due to this arrangement, the collection itself is not only a compendium of poets’ creative responses to their perspectives of the human condition, but the book itself becomes an artistic supplement to the guide already provided by the SPLC. Accompanying the titles are epitaphic initiatives for each section, also borrowed from the SPLC. Though there are slight differences between some epitaphs currently on the SPLC’s website and what’s found in the book, they’re nearly identical, their spirit equally captured in the book as on SPLC’s website.

Now, let’s talk poetry. Though I’d love to break down each section in the book, there is not enough space in this review to do so. However, the section titled Act, one of my favorite sections, is a good representation of the kinds of poetry found in Undocumented. This section (and all others) has poems that spur readers to action. The poems work together to push and prod (perhaps to puncture) the hemming of cultural and social fabrics. Sometimes the poets don’t push, they punch, as Crystal Valentine does with her “I Do Not Trust People Who Hang American Flags on their Front Porches” or Zora Howard, a Youth Poet Laureate, whose “Red White and Blue Seuss” recasts the work and spirit of Dr. Seuss but to a much different effect than her predecessor. When Carla Christopher asks, “If you can kill me, and it only counts some of the time/does it not dehumanize me/completely?” it might make readers want to join her as she takes “The Tower/down” (17). Alongside these vociferous appeals to bring “rioting . . . into the streets” (Christopher 16) are furtive attempts to unravel and rework the fabric altogether, as is the case in Karen Kovacik’s “Adagio,” where she employs the theme of knitting to suggest that though the future is “a poke,/a wrap, then slipping off . . . it’s the quietest revolution” (11). This quiet and steady reconstruction of cultural fabric is reminiscent of the writings of Michelle Alexander, who suggests such centuries-long crafting is not simply resisting social struggles to “overcome” but is meant to “create a new nation” (14). Whether it be through fervor or unabated steadiness, this section prompts action.

It should come as no surprise that Undocumented is rife with political poetry. The collection is not a stuffy history lesson or sociology class. It is pugilism. Though there are several admirable poems in this collection that take a measured approach to social reform, as is evidenced above, many flense with lines that leave you reeling. Denise Sweet warns in the introduction, “Poems are most effective when they describe and not prescribe.” When these poets employ their art to describe what they know, it’s tough medicine to swallow. Carson Borbely witnesses the body as “its own defective eraser” (28). These days, Howard D Paap sees flags that “sometimes shout/As loud as funeral shrouds” (36). Rebecca Zseder notes that because the word “‘She’ is filled with more of him than herself/She had learned how to be filled by men even before she had become a woman” (54). And how does one answer Yolanda Wisher, who asks in “the ballad of laura nelson,” based on four photographs of Nelson and her son’s lynching, “How do I protect my Boy/from that bridge/when you are protecting/the bridge with your Boy” (88).

Though nearing its third year, Undocumented is, unfortunately, as current as ever. It’s a bastion of socio-political poetry from a region whose artists humanity cannot afford to ignore. In a manner unlike any other, Riekki and Scarpino have compiled a rich, provocative, and at times dispiriting collection of poetry by some of the best poets the United States and Canada have to offer.

Alexander, Michelle. “We Are Not the Resistance.” The Best American Essays 2019, edited by Rebecca Solnit, Mariner, 2019, pp. 11-15.

Mitch James

Mitch James is the Managing Editor of Great Lakes Review.