Although we didn’t know it at the time, we were headed directly toward the dreaded North. No sir, when we five Dunegan kids, trueborn children of the South, climbed aboard Mama’s van, we were under the delusion we were aiming for Las Vegas, which was a far more desirable place altogether. We slept deeply, dreaming of Daddy and everything else we had left behind in Georgia, and woke hours later when Mama came to a sudden stop. Our heads dropped forward, and our cheeks slid along cool, damp windows. None of us wanted to leave our slumber. We were blinking, expecting to see neon lights, crowded streets, and showgirls with red sequined stilettos kicking as high as their glistening shoulders.

“Are we in Las Vegas?” At four, Mary Ruth was the youngest and noisiest.

“We’ve had a change in plans, baby,” Mama said. “Go run around a bit and then we’ll look for a nice place to spend the night.”

We all knew nice places were beyond Mama’s means, but we were grateful to escape the van. Adrian, our oldest brother and Mama’s co-pilot, stretched and yawned, while Mary Ruth took off at a run. “You can’t beat me.”

“I can so,” Luke, our five-year-old, screamed after her. “Can so. Can so.”

“Where are we, Michaelena?” Christina looked around. “Really, I mean.”

The parking lot was unremarkable. Skimmed with sand and bordered by evergreens, it was a generic piece of blacktop. We could be in Nevada. We could be back in coastal Georgia. We could be anywhere. Suddenly a splash of color flamed in my peripheral vision, and when I spun around, there was a trio of trees, one vivid red, one flickering yellow, and one totally leafless. “We’re not in the South. That’s for sure.”

We were in the North, uprooted as storm-struck trees and not a clue about where we might land. Although, after listening to Mama’s stories all my life, I had to admit the North was not quite what I expected. There were no smokestacks or farm smells or mud puddles, and, despite being October, the weather was neither gloomy nor freezing. The sky was a brilliant blue, and the sunshine softened the wind. Beyond the line of evergreens, we came to a mountain of sand. Tall as the side of a building, it blocked our way to what Mama promised was Lake Michigan. We craned our necks to watch Adrian’s white T-shirt grow smaller in his march straight up the face of the dune. Far behind him, Luke and Mary Ruth scuttled like slow-motion crabs. Christina and I started after them in long, steady strides that seemed to gain us no ground. Sand rose to mid-calf with each footfall and soon we were breathless.

“Maybe it’s a mirage,” Christina called.

Maybe she was right and nothing here was real. Maybe, like travelers stranded in a desert, we only imagined this shifting hill. Maybe Mama no longer waited in the empty parking lot and we were truly alone. Or maybe Southerners automatically found themselves lost in a moonscape once they crossed the Mason-Dixon Line.

We were panting, sweating, as we reached the summit, and the sight of our first Great Lake brought us up short. It might be real. Blue, sparkling, and ruffled with whitecaps, it stretched all the way to the horizon. Below us, the small figures of Adrian and Luke and Mary Ruth raced along its lacy edge. “It seems weird,” I said, “because we’re the only ones here. Tourist season is over now.”

“Let’s run down together.” Christina held out her hand. “Let’s run as fast as we can.”

At that moment, with the sun warming our backs and the lake wind cooling our faces, I saw my life as neatly divided as the shoreline from the water. One of those turning points Mama was always claiming for herself. A fork in the road. I was eighteen now, and I had options. I was legally free to shed Mama and my large, worrisome family like an outgrown skin and go off on my own. I could go back to Georgia and live with my best friend Muriel. I could take up residency right here in Michigan or Indiana or wherever the hell we were. I could be whatever I wanted.

But life without my family was as unimaginable as that faraway point where the lake tumbled to the other side of the world. I took Christina’s hand and we ran down the dune as light and free as helium balloons with only our legs to tether us. The wind caught my breath and brought tears to my eyes, but at the water’s edge, I wanted to keep running on through the surf and straight toward the solid navy line where the dark lake met the bright sky.

It took every single physical reflex for me to dig my heels into the surf-dampened sand and not throw myself toward that beckoning horizon. The blue of that place and the way the wind wrestled me, whipping my hair and flapping my clothes, sent an electrical charge, as shocking and familiar as any boy’s touch, from my heart to my toes. It left me dazed and wondering, and Adrian was the one to direct us all back to the van. We ran, dripping sand and lake water in pleasant confusion. We shifted back into our old places while the little kids both talked at once.

“It was the most fun,” Mary Ruth shrieked.

“Like a mountain.”

“Like a desert.”

“My legs hurt.”

“You really missed it, Mama,” Luke told her.

“Next time.” Mama smiled into the rearview mirror. She had applied fresh lipstick, which made her look wide awake and hopeful. “We can always come back.” Our van pulled away, and sand flew behind us like spray.

“Where are we going now, Mama?”

“We’ll know when we see it,” she sang. “We’ll know it’s the right place.”

We moaned in unison. We were bored with traveling. We were hungry. Mary Ruth began to howl. “I want to go home.”

I leaned forward, so Mama could hear me. “I’m eighteen, remember,” I said with quiet fierceness. “I can go anywhere.”

Mama was not impressed. “Well, I hope you will come along with us, honey.”

We zipped farther into the countryside where green fields and rows of colorful trees were broken by towns with names like New Buffalo and Three Oaks. Mama, who was deathly afraid of carbon monoxide, drove with her window cracked. Soon the sweetest smell drifted into the van and overcame us one by one.

“Oh, my.” Mama lowered her window to inhale deeply.

“What is that?” Adrian asked.

“Smells like Dimetapp,” Luke said.

“It’s grapes.” Christina pointed to a field where vines were strung between wooden posts like clothes hung out to dry.

“There’s a million.” Mary Ruth’s finger traced the window.

“Isn’t it the loveliest smell?” Mama breathed. “I thought the grape harvest was over this far north.”

The smell of grapes was as astonishing as the gigantic sand dune, so compelling I would have happily sniffed my way through vineyards all day. The spell broke when we came up on a school bus that stopped at every intersection in a town called Cranberry Spa.

“What’s a spa?” Adrian asked.

“Like a resort?” Mama suggested. “Where people go for vacations.”

“Like Las Vegas?” Christina was being sarcastic.

I concentrated on the Yankee kids disembarking from the school bus into the late afternoon sunshine. They were nothing special. They wore the usual jeans and fall jackets, T-shirts and sweatshirts, tennis shoes and fake leather boots. Clothes we Dunegans could compete with. The girls laughed and talked in exclamations and tossed their heads like girls everywhere, while the boys, middle schoolers by the looks of them, swung around the street signs and lamp posts and pounded each other on their backs. They would have older brothers, I imagined, boys with cars who never took the school bus.

Mama pulled into an old-timey gas station and went inside to buy us snacks while Adrian got out to watch a teenage girl fill our tank. “You folks on vacation?” she asked him.

“Yes, ma’am. You might say that.” He began to fool with the rear window wipers, trying to look purposeful.

“Ooh, I like your accent. Are you from the South?”

It was obvious this curly-haired Yankee girl liked talking to Adrian, the brother who had no social skills we had ever noticed. The more she flirted, the more I realized that anybody new to any small town, northern or southern, was automatically different. Not strange, as I had long thought, but interesting and at least somewhat appealing. Because we knew about life somewhere beyond this corner of Michigan, we carried an air of worldliness, a hint of the exotic.

Maybe this new insight was another sign I should slide out the van door and let my family sail off without me. I could fit in here at Cranberry Spa. I could find a job and a room to rent and get my GED. At first glance, I could pass for a Yankee. And when I opened my mouth and my drawl floated out, I would be considered charming. “Ooh,” folks would say, “I love your accent.”

Mama came back quickly, distributing food and drink like a relief worker. Then, before I could shift my brain from thought to action, Adrian left his new best friend, and we were back on the road. Colors shimmered and deepened as the sun fell lower, and again I felt a pang, a shock of recognition. I liked it here. In the North. My Mama’s traitorous Yankee genes had risen up in my blood like some long-dormant virus, and my heart was being pulled into a land which, in spite of myself, I could easily claim as my own.

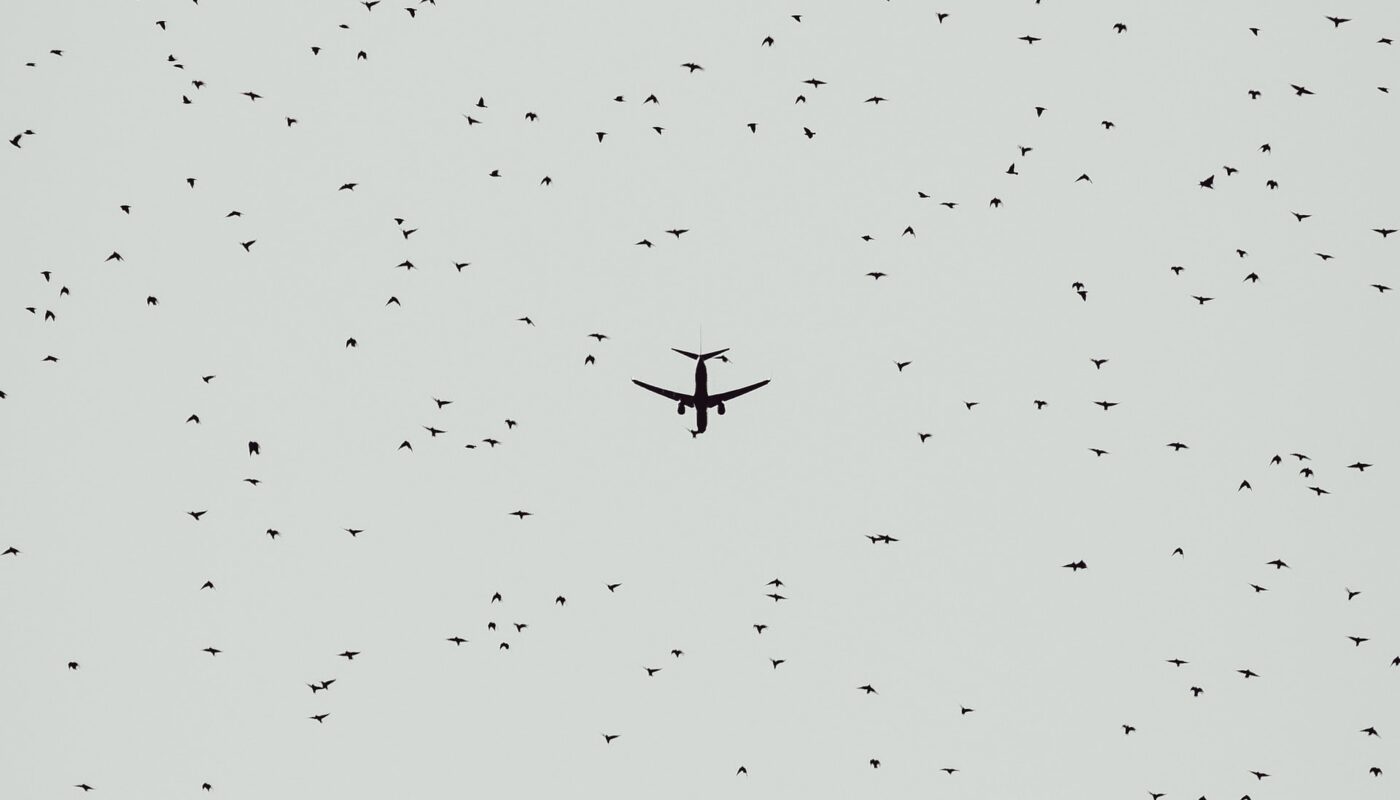

Wasn’t it just my luck that Mama and I had the same quirky instincts as a migrating bird or a spawning salmon, the same intense sensitivity as a bat or a homing pigeon? How would I ever be able to explain this disloyalty to Daddy, who was waiting back in Georgia? The sun disappeared behind us and Mama turned on the headlights, which picked up every bright tree and set it aflame. We sped down that strange, darkening highway with only those bursts of illumination, like sudden welcoming bonfires, to ease our way.

Photo by John Rodden Castillo.

Sara Kay Rupnik

A native of northwestern Pennsylvania, Sara Kay Rupnik now lives on Jekyll Island, Georgia, where she teaches creative writing for the Jekyll Island Arts Association. She holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is co-founder of Around the Block Writers Collaborative. Her collection of short stories, Women Longing to Fly, was published by Mayapple Press in 2015.

Learn more about Sara at sarakayrupnik.com