This essay is part of the Great Lakes Review’s Narrative Map project.

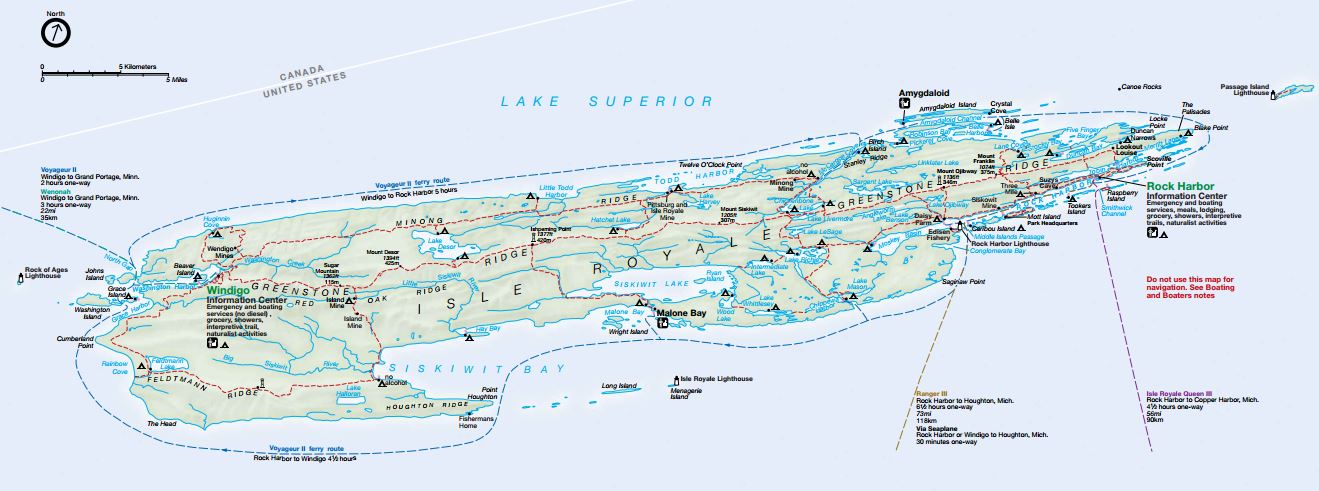

Isle Royale pokes out of Lake Superior in waves of layered rock that curve deep under the lake and emerge again 45 miles away as the Keweenaw Peninsula. These slanted rock layers create fingers of stony ridges pointing northeast. It takes a long ferry ride through Superior’s moody waters or an expensive hop on a seaplane to reach this rustic and least visited National Park. On my only visit to the island, I chose the ferry from Copper Harbor, a tiny tourist town at the northern curve of the peninsula. I didn’t really expect to see any wolves or moose during my one night stay. I wouldn’t have time to hike into the undisturbed interior, the regular stomping grounds for those people-shy species.

Approaching the island after three hours on the choppy lake felt something like that first panoramic view of Jurassic Park. When I remember it now, the theme song plays in my head. Free standing towers of eroded rusty rock guard the main island like a long string of sentries, each with a tuft of pine growing precariously from its flat top. Something here feels prehistoric and I almost expected to see the long neck of a Brachiosaurus to emerge from the tree line.Maybe it’s the thick undergrowth or the 612 species of lichens tinting the wind-scoured rocks in furry greens and oranges.

After setting up camp at the Rock Harbor Campground, I headed out for my first hike, a four-mile loop along this “finger” of rock to Suzy’s Cave. The weather in early September was idyllic for someone used to six months of winter; late season sun and temperatures in the 60s without the black flies and mosquitoes that plague hikers earlier in the season.

I’d been on the trail for less than half a mile, Superior peeking through the trees every now and then, when I decided it was already too warm for a hoodie. I was leaning down to stuff it into my backpack when some small noise made me glance around. It took me a couple of seconds to figure out that the odd brown shape behind some brush was a bull moose staring right at me from less than ten yards away.

I flashed back to the Forest Service Ranger who forced on us all of the dos and don’ts as we left the ferry. Don’t drink the water without boiling it first, don’t worry about bears (there aren’t any), and if you find yourself in a potentially dangerous confrontation with a moose, find a large object to hide behind. The logic being that a moose, although huge and powerful, is not particularly agile—they can’t dodge around obstacles to charge you. I noted a couple of lichen draped trees just off the trail, but otherwise, I was frozen. I did note that his larger furry ears (which would have been adorable in more controlled circumstances) were pointed forward rather than laid back. Just like with a horse, this was a good sign.

It was probably only a few seconds before the moose shrugged me off and went back to browsing. I probably should have ducked behind a nice big tree or boulder until he went away, but I didn’t. I discovered I was shaking when I leaned down to pull my camera out of my backpack. I was terrified. I was also exhilarated. I’d been hiking the U.P. for years and had yet to see a moose. I wasn’t going to miss the opportunity.

My camera makes small noises, clicks and beeps, but he couldn’t have cared less. He turned to check on me a couple of times during the ten minutes or so that I trailed him as he munched casually from one shrub or another, and each time I froze until my heart started beating again. When I looked at the pictures later, they were almost all blurry because my hands never did stop shaking.

Despite his size, and the wide rack of antlers, he moved through the forest quietly and precisely, almost gracefully. I calmed down enough to recognize that I was sharing this time and space with an animal that we consider “wild.” It’s something few people get to experience. It wasn’t just a fox darting off into the woods, or a glimpse of an eagle’s white feathers. We had decided together, in whatever basic way, that we were okay sharing this space. I’m not anthropomorphizing. It’s not like we shook on it or anything. I get that he was there in spite of me. Still, in those moments, he decided that maybe I was okay. I guess I made the same decision about him.

Our interaction ended when another solo hiker strode toward us from the other direction, oblivious to the wall of animal he was quickly approaching. The ranger didn’t cover what to do in this situation. If I yelled to alert the other hiker, I might also startle the moose in his direction. If I didn’t he could easily push the moose toward me. The lake was blocking a third side. Before I could decide, the moose bounded away from both of us. And, yes, “bounded” is the right verb. I began to seriously doubt the ranger’s “lack of agility” argument.

I stopped for a few excited words with the other hiker and did the rest of my four-mile loop to the relatively unimpressive cave. Granted, I was distracted. Later that day I packed up my campsite and boarded the outbound ferry. As soon as I had cell phone reception, I started texting everyone in shouty caps, “OMG I SAW A MOOSE!!!” Though I knew it couldn’t possibly do justice to the experience, that there was no way to really describe how it felt to be part of something primitive for even a few minutes, to feel like I was walking with, rather than running from something, rather than it running from me.

Rebecca Pekly

Rebecca lives and writes from Marquette, Michigan, on the south shore of Lake Superior, where she is also an associate poetry editor for Passages North. Before going back to school, she spent thirteen years working as a zookeeper. Once she was run over by a giraffe, which may suggest that she’s better suited to writing. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Prick of the Spindle, Stone Highway Review, Calliope, Dunes Review, The Chattahoochee Review, Yellow Medicine Review, and Manifest West’s Different Roads Anthology.