Darrin Doyle is a writer who proves with each new book just how versatile he can be. The Girl Who Ate Kalamazoo (St. Martin’s Press) is a magical realist novel of a girl who consumes a city. The Dark Will End the Dark (Tortoise Books) contains haunting bodily tales of consumption, violence, and darkness. And with The Big Baby Crime Spree and Other Delusions, released March 1 from Wolfson Press as part of their American Storytellers series, Doyle has rooted himself in the tradition of suburban realism. The book is in conversation with authors like Denis Johnson, Raymond Carver, and Sherwood Anderson, containing tales of an almost mythical suburbia, where a baby doll might evoke—like alchemy—the lost future that a married couple once believed in. The Big Baby Crime Spree contains five stories of faithful cheaters, down-and-out gamblers with dying grandmothers, overly-ambitious street artists specializing in chalk, and, of course, baby thievery. The shared connection that each of these stories and characters have with one another is a unique cocktail of hope and cynicism, kindness and cruelty. In under one hundred pages, Doyle delivers a collection of short fiction both cheery and upsetting, with a cast of middle-class, flawed people trying to find joy in a crushing world.

The writing style Doyle employs in The Big Baby Crime Spree is clean and well-rendered, which allows for readers to focus their attention on the images and the characters in ways that stick to their bones well after they’ve read them. The prose is lean and magical, but Doyle never lets you indulge too much in the beautiful turns of phrase and imagery. For every crisp, precise sentence, there’s a disgusting-yet-apt description of something, like this description of a character’s recently excised tumor in “The Kaleidoscope”: “It looked like a decayed potato, with all sorts of unruly tentacles sticking out here and there.” Doyle’s writing is in constant flux between the beautiful and grotesque.

The same can be said of the characters populating The Big Baby Crime Spree—none of them are good or evil, happy or downright bleak, they’re always somehow both simultaneously. These are characters who’ve faced shame, their own shortcomings, and minor inconveniences, and have come out alright in the end. It’s what makes them relatable to readers, maybe even likable in some cases, even as they do despicable things. In an especially philosophical moment in “The Art of the Dead,” Doyle writes, through the voice of his maniacal protagonist Jasper Goodwin, “Our deepest desire is not that Heaven smells of fresh-cut grass but that it stinks of rotten apples.” Whether they know it or not, the anxious, oftentimes cynical cast of characters in The Big Baby Crime Spree all hope that Heaven smells like decaying fruit because that would mean the stakes are a bit lower. That it’s okay if they miss Heaven by either a few inches or a wide margin because it isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be anyway. Like all of us, these characters are too busy existing to fit into such strict categories as “good” or “bad.”

The book begins with “The Kaleidoscope,” a story about a couple working through the culture shock of returning to the States after over a year traveling through Asia while teaching English in Japan. While Kathy quickly returns to her salaried post at the public library, Jerry struggles to find a job until, eventually, he works a woefully dead-end freelance gig covering the local culture and writing up terse reviews and profiles of various artists, bands, and theater productions. Meanwhile, he’s faced with the kind of minor inconveniences that, when stacked high on top of one another, serve as insurmountable obstacles: reacclimating to everyday life in Kalamazoo, his acquaintance-turned-landlord’s recent cancer diagnosis, and the neighborhood dogs leaving “tubular land mines and yellow sunbursts” on his lawn. As can be expected, Jerry quickly becomes dissatisfied with his job, but what is he to do? Almost as if to remind him of his powerlessness, even yelling at the dog pooping on his lawn yields no results—the dog doesn’t care about Jerry’s lawn.

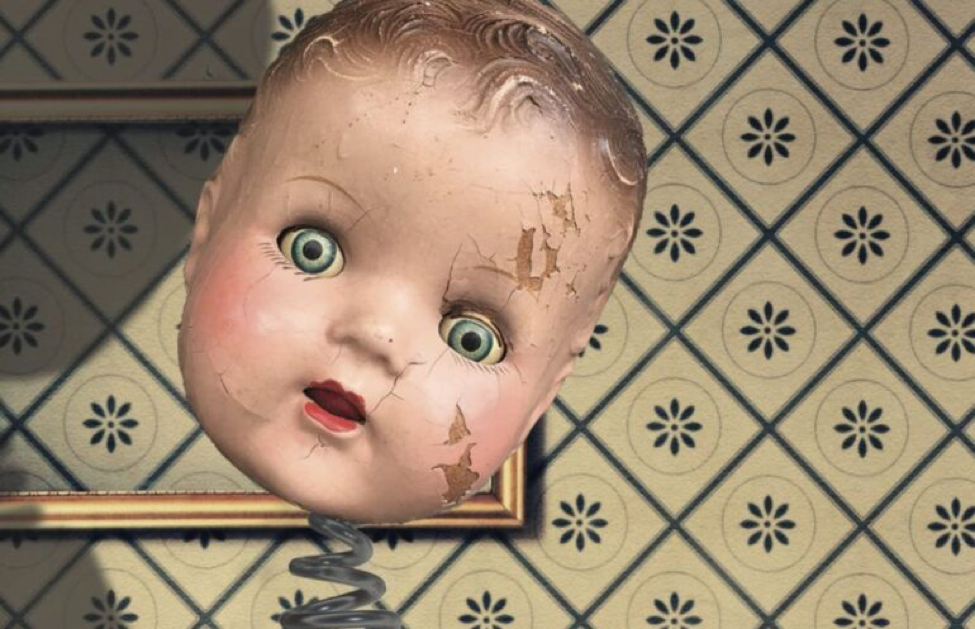

The next story in the collection, “The Baby Doll,” begins with what might be one of my favorite opening lines ever: “It was thirty minutes before sunrise, a chill on the breeze, the world undefined.” As happens each morning, though, the world becomes defined—in this case, by Gary helping his wife, Meredith, and son, Barrett, into the family car as the two of them leave for a ten-day trip to Michigan. Meredith left her teaching job to raise their son, which left Gary and his job at Boogie Records as the sole source of income. Gary doesn’t begrudge his wife that, though, for the same reasons Meredith doesn’t begrudge him his ambitions to work in television jingles, despite twenty-seven rejections from local companies in two years. This is a marriage predicated upon love, not economy. The very same day his wife and son leave town, though, he meets up with his coworker-slash-fling, Sally Vassar. The two hadn’t seen each other in over a year, but she recently started a job working alongside Gary at Boogie Records. Over the next week and a half, the two have sex time and pretend they have a life together, and Gary gets his first real chance in writing a jingle for a pizza joint. Things quickly come undone, though, when Gary finds a baby doll given to him and Meredith as a gag gift for Meredith’s bachelorette party. The doll reminds Gary of the trouble the two of them went through to have a child, and how much they’d worked for the life they now shared, and he grows to resent Sally.

Something I always admire is when a writer can masterfully write a genuinely off-kilter, unreliable narrator. It takes a willingness to give up control over a story in ways I’ve never been good at, or even comfortable with, but Doyle makes it work wonderfully in “The Art of the Dead.” The story opens on Jasper Goodwin, recovering from addiction and trying to outrun associations with his famed plastic surgeon father. He’s in the middle of working on his magnum opus for a local art festival—a chalk outline of a naked woman, meant to resemble his “Dead,” a woman whom he dearly loved— when he’s approached by the director of the art festival’s committee and told to put clothes on the figure he’s chalking. When he refuses—adding clothes would, of course, compromise his genius, his singular artistic vision—a man named Montel hoses the masterpiece away. Jasper and Cheyenne Lovely, the model who posed for his chalk outline, get drunk and head to Jasper’s apartment in the Over-the-Rhine district of Cincinnati. We learn that Jasper’s apartment is covered in renderings of his “Dead,” a woman named Greta VanderBilmenn whom he’d tutored in art and had sex with once, which led to him becoming obsessed with her. She’s the daughter of a prominent judge and Montel is her personal security guard, and she’ll do what she must to keep Jasper from ruining her reputation. Montel and Greta go to Jasper’s apartment, Greta armed with a gun, to keep Jasper quiet by whatever means she has to.

I’ve been interested lately in conceits in stories—certain character traits to which the narrative must bend, or rules of the world that characters have to reckon with—and “The Odds” is the best example of a strong, interesting conceit I’ve read in some time. It’s my favorite story in the collection. The unnamed protagonist has one dubious source of income—gambling. He’s gotten the traits of “winners” and “losers” down to a science. He bets primarily on games of pool, but also on whatever’s available: people’s ability to cross a room with a beer bottle on their heads, when a particular Rush album released, a rich man’s missed putt. This guiding rule of his life, though, is called into question when his grandmother— the last real family member he has left aside from an estranged mother—has a brain aneurysm. She desperately needs surgery, and the protagonist needs to keep money coming in, so, figuring her surgeon for a loser, he bets the surgeon that his grandmother will die in surgery. As uncaring as the notion is, he loves his grandmother dearly, chain-smoking cigarettes from worry and crying at the theme song to her favorite show.

Finally, we come to the final story: the eponymous “The Big Baby Crime Spree.” Told in enigmatically-titled sections, this story follows a hospital janitor known to his coworker as Gary in spite of his real name being Travis. Encumbered by worry and obligation to take care of his father suffering from Alzheimer’s, he hatches a plan to steal babies from the maternity ward and train them to become a coterie of baby bandits. The idea is foolproof, Gary/Travis reasons, because he operates under the assumption that babies have no fingerprints. The exact plans are hard to decipher—as they might be from someone planning to train babies in the art of thievery—but Gary/Travis wants to use them to pay for his father’s medical bills. Working full time, caring for his father, and scheming The Big Baby Crime Spree still leaves him with time for romance, though, in the form of P.N.N.F.P.—the Pretty New Nurse From Pediatrics. He takes P.N.N.F.P. on as a sidekick, discovering she has what may be an unhealthy obsession with John Lennon and has been compiling fan mail for the dead Beatle to one day, maybe, publish it as a book. In a heated argument toward the end of the story, P.N.N.F.P points out the flaws in Gary/Travis’ plans—babies can’t be trained to steal, not in the capacity that he requires at least, and they do, in fact, have fingerprints. Wow, what a sentence.

The Big Baby Crime Spree and Other Delusions is a thin volume that transports readers into a world where a surgeon would take up a bet on failing a surgery, a chalk artist can develop delusions of grandeur, and someone believes he can train babies to commit theft. In straightforward prose that elicits in readers an odd relatability with its characters, this is a collection that will neither neglect nor coddle you, primarily because, like its characters, it isn’t weighted down by notions of good or evil—it simply is. Like many people, Doyle’s characters struggle against the mundane, middle-class purgatory in which they find themselves. For readers who like fiction that can find beauty in dogs crapping on lawns, kitschy television jingles, and, yes, baby snatchers, these five delusions are for you.

J.R. Allen

J.R. Allen is a Fiction Editor with GLR.