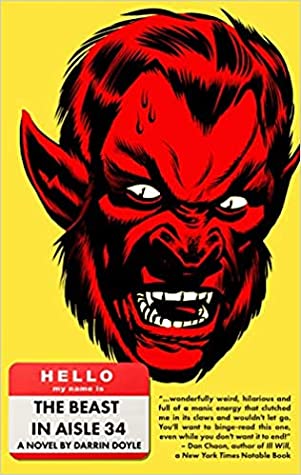

Horror has always been a genre close to my heart. As a kid, it felt like a rite of passage to watch gruesome, gory flicks with friends and pretend they didn’t scare us like hell. I’d spend the next few weeks dashing up the basement stairs so that whatever monsters might be lying in wait couldn’t grab me. I’ve horrified my wife countless times by subjecting her to all sorts of terrifying movies (our first date was The VVitch). One of the key figures in horror that sticks out in most people’s minds is the lycanthrope—a werewolf, part human, part beast, a creature that scares us not because it’s inhuman, but because deep down there’s something that is human. The same can be said about Darrin Doyle’s The Beast in Aisle 34, an ever-transforming novel about a werewolf trying to suppress his animal instincts so as to not interfere with his human life.

Horror has always been a genre close to my heart. As a kid, it felt like a rite of passage to watch gruesome, gory flicks with friends and pretend they didn’t scare us like hell. I’d spend the next few weeks dashing up the basement stairs so that whatever monsters might be lying in wait couldn’t grab me. I’ve horrified my wife countless times by subjecting her to all sorts of terrifying movies (our first date was The VVitch). One of the key figures in horror that sticks out in most people’s minds is the lycanthrope—a werewolf, part human, part beast, a creature that scares us not because it’s inhuman, but because deep down there’s something that is human. The same can be said about Darrin Doyle’s The Beast in Aisle 34, an ever-transforming novel about a werewolf trying to suppress his animal instincts so as to not interfere with his human life.

We’ve all met Sandy Kurtz. He is a middle manager at Lowe’s and lackluster husband to his pregnant wife Pat, with whom he lives in a house in northern Michigan. Like most people, he has a secret to keep: he’s been bitten by a werewolf and now has to feast once a month on whatever animals Werewolf-Sandy can get his paws on in the woods near his house. Only a few months have passed since he was first bitten, and so far, he’s pretty bad at keeping his lycanthropy under wraps. Each month he concocts a different reason as to why his wife has to stay elsewhere, or invents a trip downstate for work, leaving him free to transform and head into the woods where, usually, there aren’t any people around.

Then come the Squatch Cops—a trio of pseudo-celebrities whose meager fame came following an alleged Sasquatch sighting. Now, they’ve taken it upon themselves to canvass Werewolf-Sandy’s stomping grounds. Luckily enough, two of Sandy’s work friends, Jerry and Ben—in that order, so as not to confuse them with Ben & Jerry’s ice cream—invite Sandy to join their LARPing group. LARPing (Live-Action Role-Playing) seems like the perfect reason for Sandy to hide out in the woods overnight each month, and with his lycanthropic character, Lupus Disastrous, Sandy has a reason to traipse through the woods at night while the other LARPers sleep soundly in their tents.

As readers would expect, this goes horribly wrong, and suddenly Sandy becomes the prime suspect in a missing persons case. At this point in the novel, Doyle blends another genre into this horror-comedy cocktail: murder mystery. During his next forest foray, Werewolf-Sandy just can’t help himself when a human scent wafts through the air. It’s the Squatch Cops, diligently searching for what they believe is a sasquatch. He makes a quick meal of one of them, but afterward, Human-Sandy is just in control enough, though, to flee.

When he regains consciousness, Sandy is naked in the middle of the woods. Knowing he can’t go home just yet, he walks north until he gets to the edge of Lake Michigan and stares across the water at the Upper Peninsula. Guilty at the thought of having eaten people, Sandy flings himself into the lake, toward “A place where Sandy Kurtz wouldn’t exist anymore. He could go there. He could be free; he could be new.” Does he want to escape civilization in the densely-forested woods of the Upper Peninsula? Does he want to redeem himself and become a better person? Does he want to die?

Whatever he wants, he’s saved on the other side of the lake by a man called “Trout.” Trout has been taking good care of Sandy the last few weeks while he’s been mostly unconscious. Trout recognizes him from the news: Pat has, of course, reported him missing. It’s here the novel takes on yet another transformation, one of introspection and self-growth, where Sandy has to come to terms with the beast inside him if he wants a chance at returning to his wife, of seeing his baby, of getting his life back. From here, Sandy lives in a homeless shelter for a time, and attends a sort of “Lycanthropes Anonymous” to help him “recover” from his “addiction.” He discovers that he’s missed the birth of his daughter, and that Pat, assuming that Sandy is a criminal who is never coming home again, has moved on with someone else.

Like any good werewolf story, The Beast in Aisle 34 isn’t really about a werewolf. In Doyle’s hands, the werewolf becomes an expression of Sandy’s dissatisfaction with life. Trapped in a loveless marriage but unaware of that fact, struggling to make ends meet as a middle-manager, and without any real friends to whom he can turn, who can blame him? This is well-trod ground for Doyle, who has always found something beautiful in the banal, something mythic in the mundane. This is a novel for people who enjoy reading about down-and-out losers who keep going because they want above all else to be better than they are; or, maybe just because they aren’t quite sure what else they’d do. In tight, lucid prose that shifts between darkly comedic and macabre, The Beast in Aisle 34 transforms several times as you hold the book in your hands, becoming loving, monstrous, introspective, philosophical, funny, creepy, and always, always covered in matted fur.

J.R. Allen

J.R. Allen is a Fiction Editor with GLR.