When I spoke with Don Evans about Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry, he called himself a curator rather than an editor. His friend and colleague, the late Robin Metz, had collected poems for a Chicago anthology beginning in 2009, and in 2018 Evans inherited the project, revived it, and created something dazzling and unique: a collection of work by 134 living poets and 27 artists, all in some way rooted in Chicago. The anthology is an exciting collection not only because of luminary contributors like Angela Jackson, Campbell McGrath, Edward Hirsch, Elizabeth Alexander, Stuart Dybek, Haki Madhubuti, Reginald Gibbons, Sandra Cisneros, Luis Alberto Urrea, Maxine Chernoff, Kathleen Rooney, Ruben Quesada, and Li-Young Lee, but because each poem serves as a point on a map of imagination, offering the reader a place alongside the poet from which to experience Chicago.

When I spoke with Don Evans about Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry, he called himself a curator rather than an editor. His friend and colleague, the late Robin Metz, had collected poems for a Chicago anthology beginning in 2009, and in 2018 Evans inherited the project, revived it, and created something dazzling and unique: a collection of work by 134 living poets and 27 artists, all in some way rooted in Chicago. The anthology is an exciting collection not only because of luminary contributors like Angela Jackson, Campbell McGrath, Edward Hirsch, Elizabeth Alexander, Stuart Dybek, Haki Madhubuti, Reginald Gibbons, Sandra Cisneros, Luis Alberto Urrea, Maxine Chernoff, Kathleen Rooney, Ruben Quesada, and Li-Young Lee, but because each poem serves as a point on a map of imagination, offering the reader a place alongside the poet from which to experience Chicago.

Evans had a few rules as he selected poems. First, it would include poems by living poets, and each poet gets only one poem. He felt strongly that this was the only way to get the broad range of voices needed to best represent the city. Second, the poems must be recognizable as Chicago poems. “I made this rule because I thought there was an opportunity in the book to tell a story of Chicago, rather than just have a collection of the greatest Chicago poets; there was a story that would emerge from the collection and arrangement of the poems. I thought as I was arranging it that the poets were speaking to each other and with each other. Even though they obviously created these poems in isolation, I feel like as you progress in the book, you start to find that these different themes emerge.”

Immigration is major among those themes, as it must be. Chicago is an important landing place for all corners of the world to come to the United States. Poems are written by and about people from Vietnam, Poland, Mexico, and the American South. From Austria, Thailand, China, and Costa Rica. Regardless of where they came from, many, like Barry Gifford’s Vienna-born father, have chosen “Chicago to die in.” In a poignant account of what it’s like to talk to his mother eight thousand miles away, Ira Sukrungruang writes of how they start all their conversations with the weather and do not speak of many other things. “Our talks are ten minutes at most. In those minutes…in the whispering snow and under the breathing sun, we say what we both want to hear: I am still here.”

Social justice emerges as another theme, as in “list of wishes, first thing in the morning” by Coya Paz. She writes “I want Chicago to be run by people who love Chicago, love the people, not the real estate possibilities,” among many other things that she wants for herself and her city. Some poems speak to Chicago’s place in the nation, as does the brilliant “Chicago is Illinois Country,” by Haki K. Madhubuti: “We are the breast and chest of this nation,/four seasons on the shores of hope/where ideas and fresh water feed/hearts and land in this century’s city.” Because this is a collection organized around a physical place, well-known Chicago landmarks show up regularly, such as the Art Institute, the Museum Campus, Water Tower Place, Navy Pier, the Skyway, and of course Lake Michigan. There are also poems about unremarkable places that meant something to the poet—an intersection, a bus stop. In a sense, physical space is itself a theme, and as someone who has lived in and around Chicago for over 20 years, it was fun to encounter these places and to map them in my imagination.

Other poems are intimate, about personal experiences that seemingly mention Chicago only by chance. Poets write about the proximal, and these poets happened to be in Chicago when something remarkable happened to them. But the best poems, like the ones you’ll read in this collection, are multivalent. In Emily Jungmin Yoon’s poem “Field,” she contemplates her grandmother’s death while strolling through the Birds of America exhibit at the Field Museum. The exhibit is strangely yet utterly relevant to the moment when her mother “entered the morgue,/the only one out of her children./She watched the body getting cleaned and dressed. She observed the blues and greens/of a dead body, its cold limbs twisting out.”

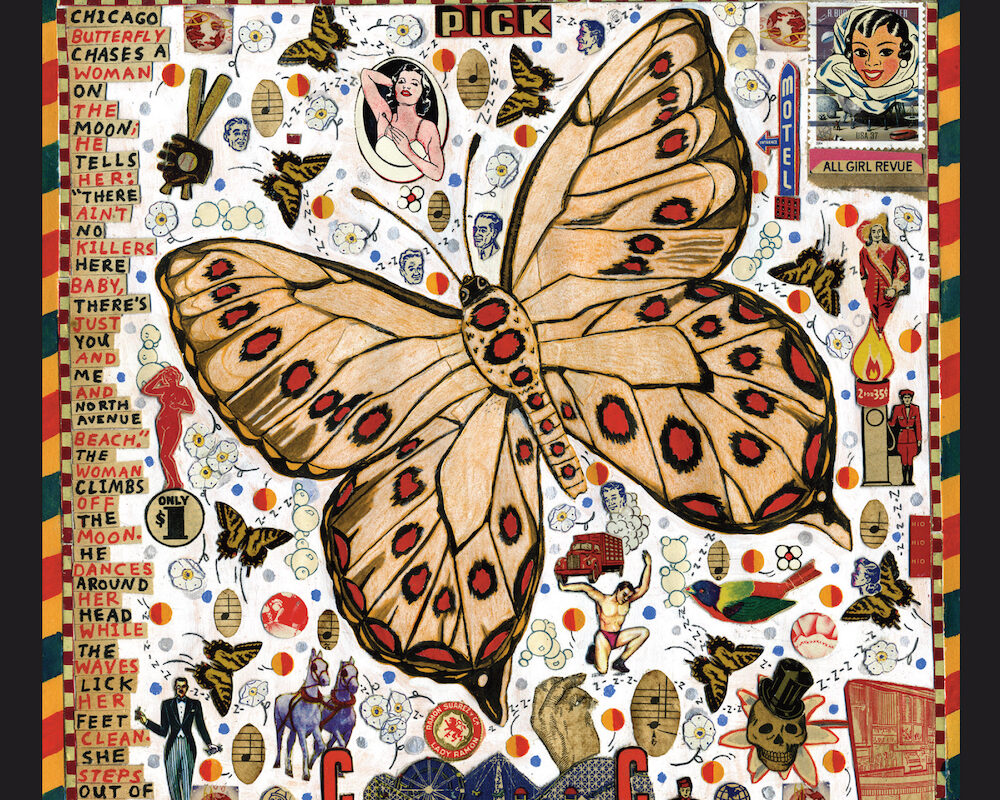

For me, some of the best points on the map were poems like Jennifer Steele’s “In Search of Butterflies,” in which the poet walks her child past the Harold Washington Library toward home after the first day at a new school, happening upon butterflies like the ones they raised at their old school; they “call out their names/and watch them fly on, unafraid/of never seeing them again.” But I also loved poems from parts of Chicago I have never really seen, like Patricia Smith’s “West Side,” in which she tells of growing up, where “West Side girls have always been enthralled/by the failed muscle of everything tasked/with ending us. Look how our butts and bellies/travel, smooth as silver on water, how we got/a million answers to the hisses from doors/of Lake Street taverns, a million ways to eat/chicken, and a million languages no damned/body knows.”

When I asked Don Evans about favorites, he likened the book to a favorite album in which the song you play on repeat might vary from day to day because you love them all. He mentioned John Guzlowski’s “Looking for Work in Chicago,” in which the poet writes about his father, a postwar immigrant from Poland who “knew he could do any kind/of work a man could ask him to do./He knew there was only work or death.” Similar to my attraction to poems that explore a life different to mine, he mentioned Tyehimba Jess’s “Long Live the Checkerboard Lounge,” place of “gyrated hip, cellar beneath/the gospel moan of Thomas Dorsey’s/precious hands-on tattered keyboard.” Don had been to the Checkerboard Lounge a handful of times growing up, and reading Jess felt like “living through his poem, what it was like for [that place] to be an integral part of life when you’re young. To be there and be part of that scene. It attracted me…I get attracted to things that I’d wished were mine.” It’s a place on the map of his imagination.

In my time living in and around Chicago I’ve heard a lot of people say they love this city (too often it’s people who leave; nothing makes the heart fond like parting). They love the food, the sports, and the beauty of a lake where you must get up early to earn the privilege of seeing the sun spread its radiance over the water—there are no easy west coast sunsets here. They love it because they’ve looked for work here, lived through long winters, navigated bus-to-El connections with gritty patience, and become converted to “good hot dogs.” It is a “beautiful cruel city,” as Mohja Kahf writes in “I Cried for You in Chicago,” but, as Vincent Francone tells the reader repeatedly in “Ashland Avenue,” you’ll love Chicago.

You’ll love Chicago

the way I’ve loved it

in my vagabond youth

and came to commit myself

fully to every mile

of the so-called second city

that I first saw

as in infant

and have since left

so many times

in search of a more

perfect plane

that I tried to manufacture

and does not seem to exist.

You’ll love this anthology of Chicago poetry, whether you’re a Chicago native, someone who has spent a slice of life here, or someone who’s only seen the city in movies. When I asked Don what he hoped for the readers of the book he said, “as a Chicagoan I enjoy having these poets be my tour guide to places and moments in history. Nooks and crannies I may have passed and never noticed. How people in a neighborhood operate.” These 134 Chicago poets will open a vivid map in the imagination for any reader.

Wherever I’m At is available for purchase at The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

Emily Updegraff

Emily is a Reviews Editor at Great Lakes Review.