You might think it grossly unfair to say that much of nature writing is boring, but let’s go there anyway: much of nature writing is boring. For every inspired Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold or Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey or Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard, there are countless tedious tomes in which some rural farmer sermonizes us on the lifecycle of the grass in his meadow or some wide-eyed wanderer shares her excitement at the colors of a foreign sunset. If you’ve ever purchased a book of nature writing hoping to be enraptured – seduced, perhaps, by an artful blurb – only to find you’ve bought an expensive sleeping pill, you know this is true. How often we find our hopes dashed! But despite the unfavorable success-to-failure ratio, nature books will continue to be published: a few of them through sheer lyricism will reveal to us those aspects of nature that we’ve previously taken for granted and strengthen our relationship with the world around us; most others will not. And as the calamity of global warming threatens to become lethal on a planetary scale, some of them, like Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert, Death and Life of the Great Lakes by Dan Egan, and Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells (2019), will rightfully scold us for the immense damage we’ve done to the planet, though such hectoring rarely translates to a wide readership given that, as a species, we seem alarmingly unalarmed by our current environmental plight.

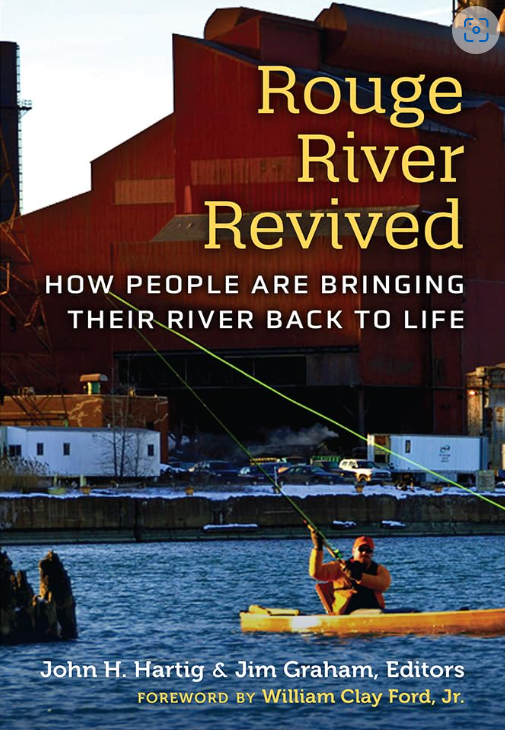

There is another, rarer subspecies of the nature book, neither lyrical nor jeremiad, and that is something we might call the environmental success story. Behold Rouge River Revived from the University of Michigan Press, which has done what academic publishers do best in offering us clear and serious prose on a significant subject, in this case, our ability to successfully band together to improve the world around us. Wittingly or not, the book is a clarion call for citizen engagement and action just when we need it most.

Rouge River Revived can be considered a handbook for post-apocalypse repair and restoration. In twelve chapters written by an assortment of scientists, environmental activists, and journalists, it recounts the tale of how citizens in Michigan banded together and, leveraging various levels of government, succeeded in fixing decades of environmental damage to a major American river that was not only sick, but poisonous. The book is utterly devoid of lyricism and sentiment and expressions of awe before nature. This is not, in short, Thoreau lounging at Walden Pond. But what it lacks in those regards it more than makes up for in inspiration and uplift. The book is a no-nonsense primer on how to help heal the planet.

The Rouge River runs generally south and southeast through Detroit, and its watershed, Michigan’s most heavily urbanized, comprises 466 square miles, in which 1.4 million people live within 48 communities. Native Americans relied on the river for drinking water and transportation, and the hunting and fishing within the watershed to help sustain the population. With the arrival of the French and English, the riverbanks were soon dotted with farms, gristmills, and shipyards. In the early twentieth century, Henry Ford built massive automobile manufacturing operations along the lower river, and other industries quickly followed, as did suburban sprawl. Soon the river was segmented by more than 60 dams. Back in the day, “pollution was considered just part of the cost of doing business,” and soon industrial waste, raw sewage, and garbage were being dumped into the river in shocking quantities. According to the authors, the federal government estimated that nearly 6 million gallons of oil and petroleum products were released into the Rouge and Detroit rivers each year between 1946 and 1948, enough to pollute nearly 6 trillion gallons of water. The Rouge became so polluted that on October 9, 1969, it caught fire.

The federal Clean Water Act of 1972 ordered that all U.S. rivers be suitable for fishing and swimming within 20 years, but little was done to help the Rouge until the mid-1980s, when two events occurred. First, the stench of the polluted water became so foul that residents of Melvindale and Dearborn, on the Lower Rouge River, could no longer keep their windows open on summer nights. An investigation discovered that the raw sewage in the river was decomposing, using up all the oxygen in the water and releasing hydrogen sulfide gas with its well-known smell of rotten eggs. Second, in 1985, a 23-year-old man fell into the river and died not from drowning, but from swallowing some of the parasite-laden water.

Undeniably, the river had become a public health risk to the 1.4 million residents of the watershed, and people demanded that something be done. They also proved themselves ready to take action. In 1985, the Michigan Water Resources Commission instructed the state Department of Natural Resources to develop a remedial action plan to clean up the river, and two local committees were also established – the Rouge River Basin Committee and the Executive Steering Committee. The Basin Committee included all 48 mayors from the watershed, as well as key legislators, representatives from state agencies, and various civic and environmental groups, including the Michigan United Conservation Clubs, League of Women Voters, and the Michigan Clean Water Coalition. The following year the non-profit Friends of the Rouge (FOTR) was established to coordinate annual volunteer river cleanup events, promote environmental education and encourage citizens’ stewardship of the river.

What followed was a 37-year cleanup effort, costing more than $1 billion, that choked off the 7.8 billion gallons of raw sewage that were being discharged into the river annually. More than 380 cleanup, restoration, and preservation projects were undertaken by 75 communities and agencies within the watershed, and more than half a million cubic yards of contaminated sediment has been removed. The frequent fish kills are a thing of the past. Today, the river has been restored, and volunteers and educators are expanding their work to improve green infrastructure within the watershed, removing invasive species, expanding riverbank stabilization efforts, and planting native vegetation to reduce erosion. As one of the book’s authors put it, “the success in the Rouge River has shown that a concerted effort from a diverse group of stakeholders can bring a river back to life.”

Now more than ever, that’s an important lesson. In clear prose backed up by rigorously compiled numbers, the book’s authors manage to make us appreciate not only the natural world around us, but the immense effort necessary to keep it habitable, and the success that is attainable, if only we try. This is the kind of nature book our times demand.

Rex Bowman

Born in Virginia and educated in small, public libraries across the United States, Rex is a translator and writer who now lives in St. Clair, Michigan, a temptingly short swim away from Canada. He has a sweet tooth for witty memoirs and wise essays and also loves to read literary nonfiction and travel yarns that emphasize people over landscape. As for fiction, his tastes are violently miscellaneous, but his favorite books have at least one of three things: unforgettable characters, fresh plots, or electric prose. He enjoys reading multiple translations of the same novel, and he relishes almost anything that isn’t ashamed to be fun (think Stella Gibbons, Richard Brautigan, Mario Vargas Llosa, Elif Batuman). Rex’s work has appeared in various literary journals, including Parhelion, Smart Set, Literary Heist, and Literary Yard. He is the author or co-author of several books, most recently Almost Hemingway: The Adventures of Negley Farson, Foreign Correspondent.