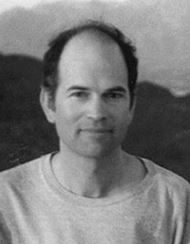

Ani DiFranco interviews painter Jim Mott about his travels, his ongoing Itinerant Artist Project, and his upcoming Great Lakes Tour. For more information about the project, visit Mott’s website, www.jimmott.com.

ANI: Maybe you could start by telling me where the idea came from for the Itinerant Artist Project.

JIM: The IAP arose out of my dissatisfaction with the marginal place of fine art in our culture. I wanted to experience something different – for myself and for art. I grew up in a home where art was valued, as were civic spirit and community service. Art-making was considered a potentially important contribution to the community.

By contrast, after grad school, my life as an artist felt too disconnected from other people’s everyday lives, and the gallery system didn’t really help; it felt too exclusive and inaccessible. I liked that some people were willing to pay for my paintings – I still do! But that wasn’t enough. And something about turning art into a commodity, buying and selling it, distorted what I thought art was all about, anyway: the exploration and sharing of meaning.

I had a lot of complaints about the relationship between art and society, and about the artworld itself. Maybe at the heart of it all was the weakening sense of community in today’s world. Art didn’t make a lot of sense to me without something like a community to work for. People sometimes leave home and take to the road to escape the influence of community; I guess I went on the road to find it.

ANI: Maybe more Woodie Guthrie then Jack Kerouac. Were you thinking of other people who had done this sort of thing?

JIM: This was back in the late-1990s. There were a few key influences that came together at that time to make me think that I could do something more productive than complaining. You were actually the first of these. I remember a conversation I had with you and Scot (manager for Righteous Babe Records) where you said if you don’t like the way things are, make something different happen. That wasn’t necessarily directed toward me, but it struck home. I’d just started on a different career track and was considering a return to painting. You joked that if I was going back into art I’d have to learn to live with other people. I wasn’t sure what you meant – probably that I could expect to be poor and would need housing – but at some level I equated it with your touring life as a folksinger: How might a painter be more like a folksinger, more connected to the people I paint for?

Around that time I heard a lecture by the art critic Donald Kuspit. He said the most important creative task facing the artist today is the creation of an audience. In the same lecture he mentioned that a lot of people involved in creative work don’t live creatively. Those were good challenges to grapple with. I’d never thought of life as a medium to work with.

Then a friend lent me Lewis Hyde’s book, the Gift, which draws on traditional cultures, folk stories, myth and poetry to make a case for the importance of gifts, the realm of gift, and gift economies – as opposed to the market economy – in the life of the community and the imagination. Hyde specifically addresses the artist’s dilemma: art is a gift that should flow freely, but to survive in a market economy we have to turn it into a commodity. The Gift helped me to see clearly the values, the dimensions of life, that commercial compromises tended to exclude – and that I wanted to stand up for somehow rather than surrender.

Together these influences got me thinking that maybe I could be a traveling artist and operate within a little micro-culture, where art could support me while functioning as a gift. It took me 3 or 4 years to actually get up the nerve to hit the road. I never wanted to travel. I get pretty anxious about going out on the road. And painting. And just about everything, actually. Touring can be kind of rough…

ANI: Yeah, yeah, it can be rough for an artist, especially a painter – you’re used to being so solitary. The social energy you expend to be interactive almost exceeds the creative energy you get to put into your work.

JIM: It’s also good input, though.

ANI: Definitely. It feeds soul more than it sucks energy. But that was something I thought about when I was considering the various kinds of art I might pursue – some seemed so exclusive, solitary and disconnected, some so connected and integral to what’s going on. That’s one reason I chose music. I think that’s similar to the feeling you had and have of wanting to be connected and relevant in this society.

JIM: Yes, but I wanted to do it with painting, because it’s what I do best. And there’s a lot of value in it, even if it’s not a mainstream medium these days.

ANI: I’ve been reading Patti Smith’s book called Just Kids. She talks about her early days in NY with Robert Mapplethorpe… Anyway, they heard that the owner of the Chelsea Hotel would sometimes exchange room and board for artwork, and so they’d show up with their portfolios, hoping for a roof over their heads. I was thinking about that, and about you, and what we’re talking about. That was 50 years ago. But even the difference between that and now: I wonder if you have the sense that I do of that being something that used to happen more, where people would place some sort of value on art that didn’t require money, where the value could change more freely, like food for art or lodging for art, whereas now that seems like an alien concept.

Like you said, people get used to thinking of everything as a commodity. I wonder if a more flexible view of art’s value was more common before our time.

JIM: I don’t know… People who get connected to my project seem comfortable with gift exchange. A lot of people think it’s fun – maybe even a great opportunity to step outside the usual way of doing things. I think I’ve told you about the judge who let me pay for my speeding ticket with art. I told him the art was worth more than the fine, so that he wouldn’t think I was getting off too easy. He said he could raise the fine if it made me feel better. How many judges are willing to have that much fun?

So there is sometimes a sense of excitement, almost of relief, at being able to do something like this, out of bounds but creative, to exchange value without money. To break out of the familiar conventions. Or to welcome a stranger into the home. To share life in a way that’s not always possible. Hospitality and gift exchange are traditional practices. A lot of people take to them naturally, they just don’t have the opportunity so much…

ANI: I think you’re right in that little encapsulation. It feels like people are…they don’t have the opportunity. That idea is not presented, it’s all buying and selling commodities, we’re living in such a commercial world. But I think there is a growing disenchantment with the isolation and commercialization of every aspect of our lives. And I think, like you were saying, there are actually a lot of people out there who just want to be connected to each other and want to have authentic experiences. And hopefully there will be more and more people like the folks you’ve come across in your travels who want to rebel from hyper-commercialism and the corporate takeover of the whole world… bartering or exchanging what they consider valuable in their own ways.

JIM: Martin Luther King said the world needs creative nonconformists. I believe he had social activism in mind more than art. And I’m afraid I don’t do enough of it outside the art tours. But creative nonconformity may be a worthwhile ideal anywhere you find a way. Lewis Hyde’s second book, Trickster Makes the World, argues that systems that don’t cultivate creative ways of exploring, engaging and reincorporating the values that the system excludes… end up becoming rigid, brittle, and self-destructive.

ANI: So, I was wondering: you’re traveling around, you’re meeting all these people, you’re in all these places and contexts, and creating all this work… and then, are you giving it all away, coming home with only a head full of memories and nothing to show for yourself? Or do you create more work than you give away? Are you doing some paintings for yourself? How does that work?

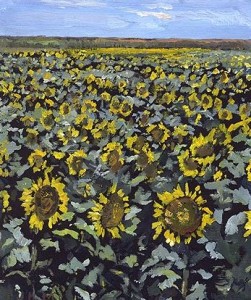

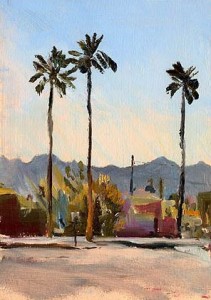

JIM: Last year I had some talks to give in Phoenix, and instead of setting up a route and all the stops in advance, I just hit the road. I used couch-surfing and word of mouth to find hosts a day or two in advance. I made just one painting at each stop and gave it to my host. I wanted to reflect more and make paintings only as gifts. Usually, though, I do a lot more paintings on tour, maybe one or two or more a day. If I stay with someone three days, that’s 5 or 10 paintings. I give one away and keep the rest.

So I’ve amassed a pretty good collection of memories, but also of paintings. The best ones are part of an IAP exhibit I’ve taken to colleges and small museums.

ANI: How do you account for the productivity? Is it because you have this audience energizing you?

JIM: That’s part of it. There’s a lot of expectation, there aren’t many distractions, and there’s a lot of incentive to paint. I’m not wondering what’s the point as much as I might at home. Something about being close to people, having an interested audience every day, making paintings in response to a life, a new world I’ve been invited into…makes me paint a lot more than I do at home.

Art in this context feels more meaningful and alive. In contrast to the view from the gallery – which is that most people don’t care about art – I’ve seen how much people everywhere can get excited about art and are curious to see what a painter might do with their world. The IAP can be a real strain, and for the most part there’s no pay attached, but sometimes I feel like the luckiest artist out there.

ANI: When you look back at these paintings you’ve done on the road, do your favorite ones coincide with your favorite people and places? I was wondering how that equation worked emotionally. When you look at your own paintings, do your favorites reflect your favorite situations and personal experiences, or do sometimes you create great paintings in your least favorite situations?

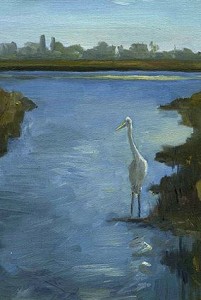

JIM: My favorite painting from 12 years of the project was done in Maine, near Acadia National Park. The place had been sunny all summer and was supposed to stay sunny all fall. Just as I arrived, a dark fog bank rolled in from the Atlantic. There was a lot of rain, and there would be rain for days. I’d been counting on painting sunny fall scenes, but it was suddenly all gray and wet. The rain got me really angry. I get mad at the universe sometimes. But I knew if I didn’t paint something get to work right away I’d sink into a pit of self-pity for my whole visit. I made myself paint something before I arrived at my host’s house. I found a subject, a rainy marsh with some spruce trees. I was probably swearing while I painted. There’s so much energy in that painting. It’s a fairly simple composition but the energy’s great, and it has some abstract power to it. So that was an unpromising situation that made me reach deeper into my reserves.

In general, though, there are all sorts of subtle factors that influence the outcome of a painting. It helps to have nice, supportive hosts. But I don’t think the location matters so much. When I was with you in Buffalo, I did that view behind the house which is just a chain link fence with some run-down apartments and some weeds… some people really love that painting.

ANI: Yeah, you have a way of evoking beauty in the simplest landscapes.

JIM: It’s interesting to try to find beauty, find meaningful engagement anywhere, and the challenge is to do that. Sometimes it’s actually harder when the scenery is picturesque. Then it’s tempting to just take dictation from the landscape and it’s harder to get into the poetic dialogue – between me, the paint, the surroundings – that for me painting is all about.

ANI: That experience in Maine reminds me of concerts I’ve had where I was just in Hell. You know, the sound was terrible and my appendix was bursting or whatever the hell, and I was just miserable. It seems like those are the shows I hear about the most. People say, “Oh, that was the most amazing show…”

I think that the energy of an artist grappling with something can be the most compelling thing of all. An artist just comfortably doing what they do in a comfortable environment is maybe not so compelling.

JIM: Yeah, something uncomfortable going on and you transcend it. On the other hand, I can feel uncomfortable in the wrong sort of way if I’m in the Rocky Mountains or somewhere spectacular trying to paint: What am I supposed to do?

ANI: Just re-recording what’s going on. It’s already perfect. Yeah.

JIM: That somehow reminds me of this Great Lakes tour. There’s a lot of natural beauty, but it’s also a rust belt kind of thing. I’m actually looking forward to some of the run down industrial landscapes, some of the subject matter a lot of people wouldn’t imagine wouldn’t imagine would be worth painting. Something in me identifies with the old structures and abandoned spaces.

ANI: It would seem to me that this upcoming rust belt tour creates the opportunity for some social commentary in the landscape. Do you have some sort of a political sense when you’re painting landscapes? Everywhere in our environment, in the rust belt, is evidence of an economy gone wrong, a nation that used to produce but now outsources… There’s so much political relevance in a landscape like ours. Does that interest you at all as a focus, or do you try to find poetry in all different landscapes? What are you thinking when painting?

JIM: In art school, and in the artworld in general, it’s been conventional wisdom that you can’t do political art and good art at the same time. Political awareness expressed through art can look too much like propaganda. If you try too hard to comment or are thinking of the commentary, it can drown out the artistic value of what’s going on. But, as Adrienne Rich pointed out – and I think Trotsky did too – if you internalize an awareness, a political or philosophical awareness, it can find effective expression through your work even without your making a deliberate attempt. If you reflect on things like politics and social inequity, that awareness will work its way into the painting integrally. And striving for responsive engagement wherever one finds oneself. That’s what I try for in painting, and that in itself is a kind of activism, a basic value.

I think my paintings at their best have a sort of existential drama going on between hope and despair, the struggle for meaning. Maybe that’s more basic than conveying political meaning, but to the extent that my paintings could also comment politically, I’d love that. But I have to trust that it will work its way into the process, rather than my setting out to do it.

ANI: Well, I guess I have a very broad idea of political. Not just news headlines. That was a really good sentence you said about the underlying existential questions in your work, and to me that has political resonance in and of itself. Even the way you approach a landscape, I think you’ve internalized it in that. For example, you’ve done pictures of the beautiful serene plains with the power lines, you know? Even the word power. It comes into m mind when I look at it. And: look at how it transforms the landscape and look at how this land is not an end to itself but a means to our conveyance of power. It resonates whether you intend it or not. It’s not like you have to have a strategy. You were just awake and responding.

JIM: Simply staying aware and responsive is primary – for us as artists or citizens – and it can be a challenge, it’s going against the trend of the mainstream culture. Ideally paintings reflect a depth of engagement, and ideally they don’t just stand on their own but contribute to a community’s sense of awareness and understanding… and beauty too, a reflective sense of what we’re living for.

ANI: Yeah yeah painting as part of the dialogue, not an individual monologue. That’s what I’m trying to do through my work, be part of a dialogue.

JIM: The dialogue is the crucial thing. So many painters I know would like to be part of a conversation, but settle for what we’ve been told, which is that “you’re painting for yourself, you’re expressing yourself.” The public seems disengaged, anyway, so why bother. One of the reasons I forced myself to go out on the road was curiosity about this – to find out how can I be a painter of little paintings and still be part of a bigger dialogue. That’s so important. How can I stand up for the relevance of this humble and contemplative pursuit in today’s world?

It’s funny – I always thought being private and withdrawn was the artist’s prerogative, maybe even a necessity. I liked keeping to myself. Then I noticed that everyone else was doing that, staying at home and watching TV, or on the computer. I figured I couldn’t complain about the decline of community spirit if I wasn’t making any effort to contribute. Also, it struck me that at times when the social fabric is breaking down, maybe artists need to take initiative in doing the opposite. I realize that’s idealistic, but we are creative problem solvers. Maybe we can turn our creative thinking and connection-making to the world beyond the canvas.

ANI: So, all of these travels, tours that you’ve done already, what part of you did they change? Did they change your painting? Did they change your person?

JIM: I’ve become a little more cheerful. I used to be depressed a lot more, partly because I was despairing about the place of art. It’s easy to think that nobody cares. But if you get out and approach it differently and connect with people in a way they can get, you see how enthusiastic they are.

But the IAP hasn’t changed my painting a whole lot. I do these little 6” x 9” paintings, landscapes, and they’re a unit of exchange and a size where I can get at least one good one done while I’m staying with someone. I’ve done more than 500 of them now, from all over. 35 states. And parts of Canada. I often wonder what kind of work I’d be doing if I trusted the studio more than the road. But there’s a certain simplicity and directness to a small, quickly done painting. And then it becomes about quality of interaction, about being there and opening up. And that’s not a bad message for art to carry.

So I’ve stuck with that. I perform at 110% when I’m on tour, creatively, socially, at all levels. I’m able to operate at full capacity and to know what that’s like as a person and artist… Plus getting to know all these great people…It’s all very affirming. It’s made me a stronger, more open person.

ANI: I love that…

JIM: I don’t know about other people, though. If you can buy into all the luxuries and fun of being disconnected, off in virtual reality all day or whatever, hanging out with a few people who look at the world the same way you do… maybe you don’t notice…

ANI: I think it’s a false front. I think it would lead to depression for anyone. You think you’re happy because you have the luxuries and fun and you have the Game Boy to distract you. But that’s something I’ve been trying to communicate to people. The process of leaving your house and engaging with people and giving your energy to something bigger than yourself… and you do it to make yourself happier. Yes, you do it to make the world a better place, but trust me, you also make your world a better place. I think if people really knew that they might be more attracted to the hard work of it.

JIM: that’s the great thing. If you can do what you do well and connect it with other people’s lives, it’s rewarding. The paradox of the more selfless you are the more you really get back. Maybe selfless isn’t the word. I don’t feel selfless. But my project gives me a way to put myself in the service of something more important than myself…

ANI: Focus on something other than yourself and you shall heal yourself.

JIM: Hey, is that a good thought to end on?

ANI: Yeah, I think so.