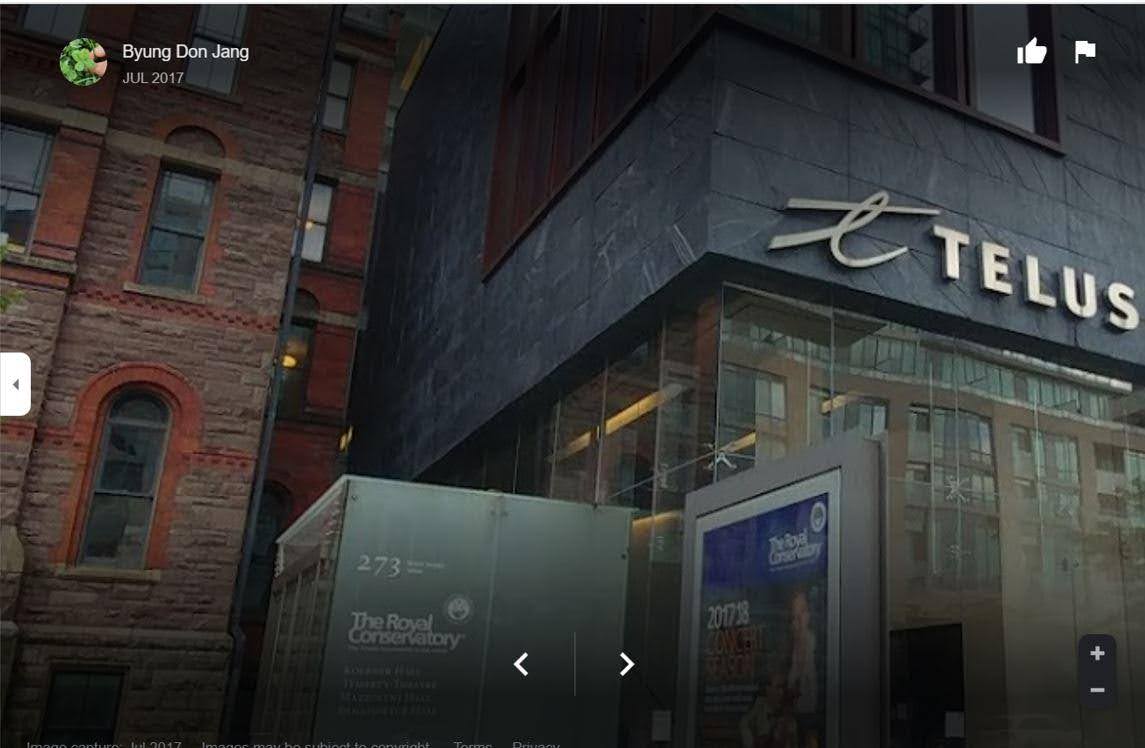

What if E. M. Forster’s plea to reach out to the Other—“Only CON-nect!”—comes with a hyphen and a first-syllable accent that expose the exhortation as a con game unbeknownst even to the (con) artist? Forster’s A Passage to India (1924), after all, projects his closeted homosexuality onto the South Asian “queer nation.” A flaneur for a week in downtown Toronto as lost as a British tourist in India, a Taiwanese in the Canadian metropolis bursting at its seams, with new construction at every street corner, I was struck by old Toronto buildings of brick and mortar “glued” with a generous application of strips of caulk to ultramodern annexes of glasses and steel, so much so that Toronto appears to be a city cobbled together with caulk. Caulk serves to bind hundred-year-old stone and brick to twenty-first-century glass and concrete. Figure 1 shows the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, built in the 1880s, and the adjacent TELUS Centre for Performance and Learning, completed in 2009. The “seamless” connecting tissues seen from Bloor Street in Figure 1 comprises, upon closer scrutiny in Figure 2, a deep cut into the Conservatory’s stone walls to insert metal bars holding glass panes, sealed tight with caulk, away from the public eye. Figure 2 indicates how far my hand thrust into the gap chiseled to secure glass panels.

This practice on the body of the city reminds me of medical procedures on the human body, such as tooth implants, coronary stents, or hip joint prostheses to sustain, even amplify, the life of the old. I wonder if caulking heralds an organic growth from the past or simply confuses architectural/artificial implants as a fusion of the past, present, and future. Refusal to contemplate the latter scenario may lead to an obliviousness to, in a manner of speaking, cancerous tumors out of old bones and tissues. Of course, a cancerous growth, left unchecked, sires a life of its own. What used to be disparate entities is taken over by a new arrival that multiplies on the host body. This has happened throughout human history, most recently the colonial-settler civilizations overtaking the indigenous land and people. Hence, millennial ultramodernity metastasizes from the white Euro-centric tradition’s faux classical Greco-Roman architecture of columns and cornices wherever flaneurs cast their eyes. But the fusion of tradition and modernity is deceptive.

The twenty-first century is determined to see the grafting of the old and the new as “organic,” or rather, determined not to see the jarring suturing. Right next door to the Royal Conservatory of Music is the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) built in the 1910s with its flamboyant 2005 Libeskind addition, called the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, named after the Jamaican Chinese Canadian philanthropist. Figure 3 is the preferred frontal view of the ROM. Looking up at the juncture where Libeskind affixes his canted domes, Figure 4 zooms in on the cut concealed by aluminum bands with, conceivably, ample caulk underneath. The darker color of the stone along the edges of the aluminum suggests more recent incision yet to be bleached by the elements. Taken at the far end of the admissions area inside the Libeskind-Crystal lobby, Figure 5 bares the haphazard, makeshift nature as the boards covering up the base of the original ROM walls ill-fit the stone structure, leaving half-inch gaps up and down between the board and the wall, between the new ROM and the old ROM. If suturing on the exterior amounts to a trompe l’oeil, deceiving the eye as one organic whole, its stitches on the interior expose the holes glaringly, so long as the museum security let the curious tourist wander to the far end without any exhibition, which is an unintended exhibition in and of itself.

Whether yoking East and West, Forster and India, tradition and modernity, connections oftentimes resemble a marriage of convenience based on mutual interests rather than romantic love and attachment, based on taking rather than giving. Insofar as the old and the new are concerned, “only connect” comes across as nothing but feel-good empty rhetoric when one side, like the Royal Conservatory’s stone wall, can only scream in a frequency much higher than the range of human comprehension when the teeth of the electric saw bite into it. Most modern annexes, nevertheless, rarely go to such extreme at an exorbitant cost. They simply plaster gray silicone caulk along the vertical aluminum casing between the old brick and the new glass.

The standards of the organic in critiquing the caulk city may sound passé in the posthuman era, where the nonhuman inorganic cries out to be recognized beyond the conceptual constraint of the Anthropocene. The notion equating the organic with the good meets further challenges as to what exactly defines a healthy, living organism. What about humans barely living, or the “subhuman” homeless, priced out and evicted by gentrification of luxury condos and high-rises in the caulk city? Tent cities in city parks as well as drunken and rambling paltry things on the doorsteps and front stoops are symptomatic of the detritus of modern progress. Imagine my shock venturing to Allan Gardens only to find the shanty town! Retired Presbyterian minister Michael Stainton joined me in a walk across Allan Gardens. Introducing me to the statue of Robert Burns in memory of the heritage of prosperous Scottish immigrants near Cabbagetown a century ago, Michael meets his doppelganger on the left, the one with no hat, in Figure 6, whose forearm was tattooed with Maike (麥克 “Michael” in Mandarin). Dwellers of the Gardens’ tent city, Maike and his drinking buddy invited Michael to take pictures of them with the cell phone.

A strange (con)fusion occurs: an ex-missionary to Taiwan, Michael, photographs Maike at the base of the statue dedicated to a Scottish poet, whose descendants multiply to dispossess Maike and the like, who have congregated to the nearby Miziwe Biik Aboriginal Employment & Training and other native social services. Apparently unemployed and unemployable, Maike chose to tattoo his Christian name in Chinese. Caulked together are not only tradition and modernity, old stone and new glass, but also East and West, haves and have-nots. Rather than a marriage made in heaven, this seems a hell on earth. Rather than “Toronto chic” flaunted by the fashion industry, urban developers, and other cultural practitioners, this may well be “Toronto shit” for Maike and for the gentleman who beat a strange tune on the road sign with a metal pipe to his wee-hour shouts of “Fuck.” Occupying a street corner blocks from Toronto Metropolitan University, formerly Ryerson University à la the residential school mastermind and Methodist minister, this gentleman trailed after me one night, repeating “Fucking Gook,” a distant echo from the Vietnam War. I was tempted to turn back to tell him that I was not Vietnamese, but that might have thrown him off as much as he did me with the epithet. How do I connect with him? How do we reach out, without conning the other side as well as ourselves?

Photo by Patrick Baum on Unsplash.

Sheng-mei Ma

Sheng-mei Ma (馬聖美mash@msu.edu) is Professor of English at Michigan State University in Michigan, USA, specializing in Asian Diaspora culture and East-West comparative studies. He is the author of over a dozen books, including The Tao of S (2022); Off-White (2020); Sinophone-Anglophone Cultural Duet (2017); The Last Isle (2015); Alienglish (2014); Asian Diaspora and East-West Modernity (2012); Diaspora Literature and Visual Culture (2011); East-West Montage (2007); The Deathly Embrace (2000); Immigrant Subjectivities in Asian American and Asian Diaspora Literatures (1998). Co-editor of five books and special issues, Transnational Narratives (2018) and Doing English in Asia (2016) among them, he also published a collection of poetry in Chinese, Thirty Left and Right (三十左右).